SAN LUIS RÍO COLORADO, Mexico – The sun still hides beyond the desert’s dark horizon as Jaime Escalante Galvez, his wife Leydi Gonzalez and their 2-year-old daughter, Adriana, slide through a bucket-size hole under a border fence and squeeze into the United States.

The Guatemalan family is fleeing poverty and, they say, armed thugs who regularly stole half of Escalante's earnings as a $45-a-week minibus driver. The U.S. promises a better life, security, stability.

Or so they hope.

Just a few hours later, on a steep riverbank 1,300 miles to the east, Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his 23-month-old daughter, Valeria, wade into the swirling Rio Grande at Matamoros, Mexico. They left their native El Salvador two months prior and ended up crammed into a border shelter with hundreds of other immigrants. Desperate and frustrated, Martinez has decided to try their luck with the river.

But the muscular current sweeps them away. His wife, watching in horror, cries out from the river's edge. Search teams find their bodies 12 hours later, 500 yards downriver. Valeria’s tiny arm still clings to her father’s neck. Soon a photo of their river-swollen bodies will reverberate around the world.

Two families. Two scenes. One barely noticed, the other unforgettable.

Both moments surfaced during a week when the USA TODAY Network launched a team of nearly 30 journalists to begin a comprehensive examination of the migrant crisis along the U.S. southern border. The unprecedented effort revealed an immigration system on the brink of collapse.

For seven days, the reporting teams documented – hour by hour, scene by scene – the complex issues that have combined to create a precarious scenario for the United States and nations to the south that are grappling with undocumented migrants. The consequences and implications were clearly visible at times and dangerously hidden at others:

Strained and exhausted aid groups struggling to manage shelters choked with twice as many people, or more, as they were built to house. Border Patrol agents thrust into roles they aren’t trained to handle. Immigration courts overwhelmed – with seemingly no manageable caseloads in sight and no chance at swift justice. Local governments scrambling at their own expense to feed and house migrants abandoned in their cities by the U.S government, with costs swelling into the millions. And, day after day, migrants staring down death and hardship in their search for a better life.

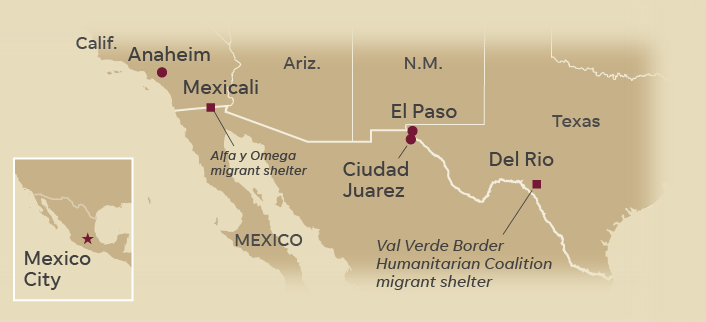

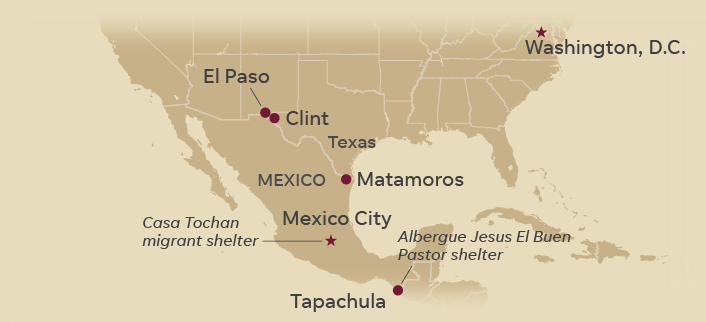

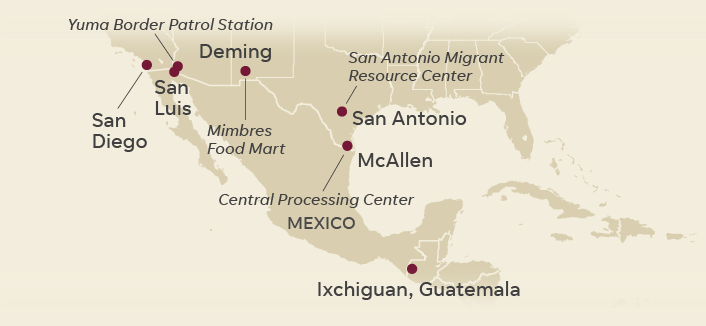

During the week-long effort – from June 24 to 30 – the teams reported from four countries and six U.S. states. They traveled more than 20,000 miles – including to the highlands of Guatemala, the National Palace in Mexico City, locations on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, immigration courts in Los Angeles and the lawmaking chambers of Washington, D.C. – digging deep into a crisis years in the making.

Previous U.S. presidents have grappled with waves of migrants who show up at the border. But the federal government's actions since President Donald Trump took office in 2017 – including limiting asylum requests and separating children from families – have left border officials ill-equipped to respond and have put migrants at unneeded risk, creating a scenario that serves no one well, according to local government officials, immigration lawyers, longtime border residents and immigration policy experts.

“It hasn’t been treated as a whole-government emergency response,” said Theresa Brown of the Washington-based Bipartisan Policy Center. “It’s been treated as a border security problem. That’s exacerbated the problem.”

This year, the sheer number of migrants who arrived – especially families – overwhelmed U.S. Border Patrol facilities. In the first six months of 2019, federal agents apprehended 534,758 migrants at the southwestern border – the highest six-month tally of any year since 2008, according to Border Patrol statistics.

The administration notes that apprehensions were down in August, year over year, and points to that as a sign that the Trump presidency has slowed the flow of immigration. But the consequences of the 2019 surge will ripple through the immigration system for years, and the administration's recent move to block asylum almost entirely seems certain, experts say, to put more migrants at risk.

The week began with the death of a father and daughter. It will end with five more recorded deaths of migrants in the U.S. and untold deaths of others along the way. In that time, a young mother will become disillusioned by life in the U.S. and consider returning home. Federal authorities will release thousands of migrants, who will board buses and planes and scatter to cities across the United States. A shelter director will struggle to keep migrants in his care from being kidnapped or raped. A family in El Salvador will bury their loved ones.

And still, each day, more migrants begin their journey north.

Monday, June 24

7 a.m. Escalante, Gonzalez and Adriana awake in the Yuma Border Patrol Station in Arizona, known as la hielera, or "freezer," named for its frigid temperatures.

The previous morning, after slipping into the U.S., the Guatemalan family trekked under a blistering sun and were picked up by Border Patrol agents, along with 35 other migrants. The agents bused them to the Yuma Station.

The family spent the night in separate chain-link holding cells. Escalante, 35, shared a single juice bottle with 50 other men in his crowded cell. Gonzalez, 29, and Adriana shivered through the night on the floor of a different cell, forced to sleep on their sides because of the limited space and hugging for warmth as another woman’s feet brushed Gonzalez's face.

There were no mattresses, and the bathroom had no soap.

9:30 a.m. - Andrea Delgado, a Mexican health worker, kneels on the floor at the Alfa y Omega migrant shelter in Mexicali, Mexico, over the border from Calexico, California. She gently holds a finger of 6-year-old Maritza Salazar Lopez and leans in to prick it. “It’ll be quick,” Delgado promises.

Maritza has been vomiting and hit by recurring fevers. Health officials want to test for malaria.

Maritza and her mom, Marisela Lopez, arrived at the shelter in March, when U.S. immigration officials sent them to Mexicali under the Trump administration’s Migrant Protection Protocols rule. The policy, enacted last year, requires all non-Mexican migrants requesting asylum along the southwestern border to return to Mexico to await their day in immigration court, which can take months.

Lopez and her daughter fled Guatemala to reunite with Maritza’s father in Maryland. After arriving in Mexico, both mother and daughter contracted chickenpox during an outbreak at the shelter. Lopez missed her first asylum hearing in May because, she says, U.S. officials saw blisters on her face and body and denied her access into the country. She doesn't know how to get a new court date.

At Alfa y Omega, people wash their clothes in a large sink and then hang the wet laundry from all possible corners. Some seek shade from the relentless sun. By late afternoon, the shelter manager makes a big pot of soup and offers bowls to the migrants.

After her evaluation, Maritza is rewarded with two lollipops. That night, with triple-digit heat outside and no air-conditioning inside, Maritza and her mother squeeze together with 450 other migrants and sleep on thin mats on the ground, surrounded by their few belongings.

9:52 a.m. - Judge Lori Bass’s 17th-floor courtroom in Los Angeles Immigration Court is crammed to capacity. Among those seated: Yenelin Guadalupe García Solval, 19, from Guatemala, who has lived in Anaheim, California, for more than two years with her mother and stepfather. She and her brother, Elvis, 14, fled an abusive father and crossed the border to live with their mother.

As of June, García Solval’s immigration case was one of more than 908,000 pending across the United States, according to the TRAC Immigration Project at Syracuse University in New York. That's nearly twice as many cases as were pending nationwide just three years ago.

Outside the downtown courthouse, lines form as early as 6:30 a.m. Immigrants – some accompanied by lawyers, and all dressed in courtroom attire – wait patiently for the doors to open.

Judge Ashley Tabaddor, head of the National Association of Immigration Judges, says she and other judges are drowning in cases. On a maroon sofa in her Los Angeles office, more than 40 thick case files – all unreviewed – tower in a neat stack. Tabaddor says the backlog at times is daunting. The federal government expects her to complete 700 cases a year.

“They don’t really account for the out-of-court time we need, which, as you can see, is a lot," Tabaddor says, picking up the stack of paper and dropping it back on the couch.

Inside Bass' courtroom, García Solval tells the judge she’s seeking asylum because she is a lesbian. In Guatemala, she says, that means she’s harassed at school and everywhere else.

Bass looks over her notes, the only sounds the soft hum of a copying machine in the courtroom and the shuffling of papers. Finally, the judge leans into her microphone.

“Your case is being terminated because asylum has been granted,” Bass says. She adds, “Congratulations.”

A smile spreads across García Solval’s face.

1:45 p.m. - A Honduran woman, Elsa Ondina, splashes water from a garbage can onto her 8-year-old daughter and 5-year-old son. The can holds drip water from a leaky air conditioner in the courtyard of the Val Verde Border Humanitarian Coalition migrant shelter in Del Rio, Texas. Using soap, Ondina scrubs one child, then the other.

They arrived at the shelter the day before. Soft-spoken, Ondina says she left Honduras to escape gang violence. Her children weren’t able to go to school, and they lived in fear.

Since arriving in Del Rio, baths have been a rarity. Today, shower facilities at the shelter are locked.

“Don’t use that water – it’s dirty,” a volunteer tells Ondina in Spanish.

She shrugs and splashes more sudsy water on her son.

2:41 p.m. - Border Patrol Agent Mario Escalante stops his SUV along a border fence in El Paso, Texas, when he sees a woman with two children sitting nearby. The woman says someone in Mexico tried to stop them. Unsure whether they were Mexican military or drug gangs, she and her children ran across the Rio Grande into the U.S. The river was shallow with tall brush.

“It’s OK, you’re in the U.S. now,” Escalante tells her in Spanish.

Escalante grew up in El Paso when the river was wider and there were no fences. He would cross the international bridge into Juarez with his abuelo, or grandfather, who owned businesses there. He never dreamed he’d be patrolling the border someday.

Escalante drives the migrant family to the processing center near the Paso del Norte International Bridge. “At the end of the day,” he says, “we have a job to do.”

3:45 p.m. - Esperanza Panameño, 34, and her husband, Carlos Salinas, 43, huddle in the Good Shepherd shelter on the outskirts of Juarez and ponder the bank-issued debt hanging over their heads.

To finance their trip from their native El Salvador to the U.S. border, the couple secured $4,000 in loans over two years from Banco Fomento Agropecuario, a state bank that provides low-interest loans to farmers. Many migrants use the money to flee north.

The bank charges the couple 9% interest, they say. A private bank, Caja de Crédito, charges them 42% interest on another $2,000 in loans, according to the couple.

The couple, along with their three children, crossed into the U.S. in June, spent five days detained in El Paso, and then were sent back to Juarez under the Migrant Protection Protocols while waiting a hearing on their asylum claim.

The couple’s first hearing is scheduled for December – six months away.

Panameño says organized crime has taken over nearly every corner of life in their hometown, including the right to wash clothes in a nearby river. But waiting in Mexico seems even riskier. She and her husband are considering returning to El Salvador, despite the consequences.

“We were doomed there,” she says. “We came here for a better life.”

Tuesday, June 25

8 a.m. - In McAllen, Texas, Mayor Jim Darling checks his email for updates from the Border Patrol and nonprofit groups about the crush of migrants arriving in his city.

The Rio Grande Valley has absorbed most of the recent surge of undocumented migrants: There were 43,205 apprehensions here in June, more than double that of any other sector along the border, according to Border Patrol statistics. The city has set up barricades on the international bridge to stem the flow of migrants crossing into McAllen, narrowing the four lanes to one and slowing commerce to a crawl.

The city lost around $100,000 in toll revenue from the lane closures. Businesses, many of which rely on goods and customers from Mexico, saw sales drop.

“We’re expecting the Mexican government to control the southern border, but we can’t even control one lane on a bridge,” says Darling, who doesn't identify as Democrat or Republican.

Darling isn't new to migration-related dilemmas. In 2014, his city spent more than $600,000 providing tents and transport and retrofitting showers for Catholic Charities, a local group that deals with migrants, as waves of unaccompanied minors arrived at the border. He sought reimbursement from the federal government but said he's only received $175,000.

Some U.S. cities have drawn controversy for becoming so-called sanctuary cities, prohibiting local police from asking about immigration status or cooperating with federal agents. A Texas law says it is illegal for cities to refuse cooperation with federal immigration officials.

“We’ve taken a lot of criticism for being a sanctuary city and we say, ‘We're not a sanctuary city and you ought to be grateful for what's happening here,’ ” Darling says.

8:18 a.m. - At his daily news conference in the north wing of the National Palace, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador says he will deploy 15,000 active-duty soldiers and federal police to Mexico’s northern border.

Questions about Mexico’s immigration enforcement policies have become a fixture of these early morning news conferences, ever since the government reached a deal with the Trump administration to curb the number of migrants reaching their shared border.

Reporters question whether Mexico is simply doing the Trump administration’s bidding.

“We have to avoid a confrontation with the United States,” the president says, adding: “We don’t want (a trade) war, we don’t want confrontation. We have to act with restraint."

Later the same day, in the Oval Office, Trump will field questions from other reporters about border security. Lamenting how drug cartels and coyotes take advantage of migrants, he says, “It’s horrible what they are doing to young children.”

“So I just want to thank Mexico," Trump says. "They’ve really done a great job. We appreciate what they’re doing.”

8:56 a.m. - Two dozen families walk into the Iglesia Cristiana el Buen Pastor in Mesa, Arizona. They’re from Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala, Belize and Cuba and were recently released by federal immigration agents. Some wear ankle monitors. They will remain in the United States while their asylum cases are pending.

Pastor Héctor Ramírez reminds them to keep their documents organized and not to share them with anyone. He stresses the importance of attending all court dates and of not fearing the police. He advises a family headed to Florida not to go swimming while wearing the monitors. Some families head out to purchase bus tickets to their final destination.

Fourteen migrants walk up to the altar and kneel in prayer. Many are crying, their chests shuddering with stifled sobs.

12:41 p.m. - In a former World War II hangar in Deming, New Mexico, Anthony Torres, pastor of Alamogordo Mountain View Church, hands out white Styrofoam boxes filled with fajitas, beans and rice to hungry migrants seeking asylum. The hangar is temporarily housing about 7,000 migrants – which amounts to about half of Deming’s permanent population.

As of May, Border Patrol had released 170 migrants in the city, overflowing the church and other facilities. That month, the City Council voted unanimously to declare a state of emergency.

This conservative-leaning community is one of the poorest in the country, with a median household income of $25,428, compared with the U.S. average of $57,652.

The pastor says he doesn’t know whether he’s witnessing a crisis, only that people need help. “Every church needs to respond to all needs of the people,” Torres says.

Torres pointed to Matthew 25:35-40, a Bible verse painted on the portable kitchen’s side doors. It describes giving food, drink and clothing to those in need.

Kevin Villanueva, 22, of Honduras, sits at a table with his 5-year-old son, Carlos, and digs into his lunch. Days earlier, he hoisted Carlos on his back and waded across the Rio Grande and into the U.S. His wife and daughter crossed two days later. He hasn’t seen them since.

He’s hopeful they’ll be reunited soon but has no way of knowing. They don’t have mobile phones. The four left Honduras a year ago to escape criminal groups, Villanueva says.

“I just want a chance,” he says. “God willing, I will have an opportunity.”

To get to the U.S., the family worked in small businesses and shops along the way to earn cash. Mexican police were the worst, Villanueva says. They would hit him and try to extort his cash, he says.

“They said, ‘I could kill you and throw you in the river and no one would care,’ ” he says.

3:15 p.m. - In Del Rio, migrants sit in folding chairs in the small lobby of the nonprofit Val Verde Humanitarian Border Coalition, listening intently as volunteer Mario Hernandez gives instructions in Spanish.

The Texas city of about 36,000 residents has a Stripes gas station that doubles as a Greyhound stop. Hernandez explains that the migrants must pay $45 each for transport to San Antonio, which has better transportation options to other locations where they might join family or friends while they wait for asylum cases to be decided.

Some of the migrants – mostly Haitians and West Africans – nod in agreement. Others stare blankly at Hernandez.

In the Border Patrol's Del Rio Sector, the number of families apprehended is up more than 1,100% so far this fiscal year – 30,000 families, compared with 2,500 the previous year.

In the past few weeks, most of the migrants have been making their way to the United States through Mexico. Today, for the first time, the volunteers have welcomed Nigerians.

The shelter sometimes uses a French-speaking volunteer to speak with the migrants, but his availability is limited. Most Haitians know enough Spanish to understand Hernandez’s speech.

Finally, a Nigerian man raises his hand. “Do you speak English?” he says.

4:09 p.m. - Three Mexican military soldiers and a Federal Police officer, stationed under a bridge about 5 miles north of Tapachula on Mexico’s Pacific Coast Highway, stop a red pickup traveling north. A Mexican immigration officer with the soldiers questions the passengers, then allows them to pass.

The soldiers are part of the newly formed National Guard – the Mexican president’s answer to the waves of undocumented migrants passing through his country.

The soldiers aren’t trained in immigration rules and have created a bottleneck of thousands of migrants in places like Tapachula, says Enrique Vidal, an immigration lawyer and advocate. The Mexican government “is trying to deport them quickly without giving them a chance to make their claim,” he says.

At the checkpoint, the troops stop every suspicious-looking car. The corridor is popular with migrants traveling north toward the U.S.

What happens when they encounter migrants?

“They are rescued,” says the immigration officer, meaning they are taken to an immigration station on the outskirts of Tapachula, their outcome often unknown.

4:20 p.m. - Pastor Hector Silva strolls through the rows of camping tents in the courtyard of the Senda de Vida migrant shelter in Reynosa, Mexico, across the border from McAllen.

Migrants from Cuba, Venezuela, Guatemala, Honduras and West Africa rest in the sweltering tents in 98-degree heat. The shelter, built to hold 500 migrants, lately has held 800 or more.

Since the Trump administration began its “metering” policy at the border – only allowing a small number of migrants to enter U.S. ports of entry to legally request asylum each day – Reynosa has been a bottleneck for thousands of migrants in one of Mexico’s most dangerous cities, which crawls with warring drug cartels and armed gangs. Mexican immigration officials make things worse, Silva says, by randomly selecting who may cross – and who stays another day.

Migrants at the shelter have been kidnapped, beaten up and extorted for money if they venture outside, Silva says. Some have been waiting more than three months to meet with U.S. immigration officials, he adds.

“We are witnessing a crisis,” he says, “and the crisis is the waiting.”

In February, 60 nongovernmental organizations in Mexico, Central America and the United States sent a letter to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security decrying the “Remain in Mexico” program. The letter read: "Civil society organizations and migrant shelters have documented multiple cases of torture, murder, disappearances, kidnappings, robbery, extortion, and sexual and gender-based violence that migrants and asylum seekers suffer at the hands of criminal groups in Mexico."

Erner Luis Avila and wife Yeslin Soto arrived in Reynosa from Cuba two weeks ago. Before even reaching the migrant center, they were kidnapped by gunmen and taken to a stash house on the outskirts of town, Avila says. Family members, he says, wired the couple $3,000 for their release.

“We never thought something like that would happen to us here, so close to the U.S.,” Avila says. “We’re terrified.”

4:40 p.m. - Oscar Gutierrez, 25, of Honduras, hoists an 80-pound bag of cement on his shoulder at a home construction site in a tony neighborhood of Memphis, Tennessee.

Gutierrez entered the U.S. without documentation last year. As he awaits his asylum hearing, he doesn’t yet have a work permit – but that doesn’t stop businesses from hiring him.

“One week, I pay the lawyer,” he says in Spanish. “The next week, I pay rent; the next week, I pay for the car. The next week, I have to send money to my daughter.”

Gutierrez amassed a $9,000 debt getting himself, his girlfriend and daughter to the United States. He knew little about construction when he started. He makes $12 an hour and works about 55 hours a week.

He says, with a smile, he feels good. “Always.”

He pours the concrete into a fence-post hole, sending up a small cloud of powder, then adds water and mixes it with a big stick and chunks of stone before moving on to the next hole.

9:30 p.m. - For weeks before her family’s journey to the U.S., Leydi Gonzalez, the woman who squeezed under the border fence, lit candles to the Virgen de Guadalupe and prayed her family would be able to leave Guatemala. “Many people cross and many don’t,” she said, referring to those who are abducted, get deported or die along the way.

Now, after claiming asylum and being released from a U.S. detention center, she boards a flight from Arizona to Newark, New Jersey, with her husband, Jaime Escalante Galvez, and their daughter to stay with relatives. The plane ascends, leaving Phoenix’s sparkling lights behind. Jaime and Leydi sip complimentary Cokes and laugh quietly. They’ve made it.

Six hours later, Gonzalez hugs her older brother, Elder Gonzalez, in the baggage claim area of Newark Liberty International Airport. It’s the first time she’s seen him in six years.

Her toddler, Adriana, smiles when she sees another uncle, Abner. Until now he’s been nothing more than an image on her mom’s phone during weekly WhatsApp video chats.

As the family reunites, Escalante lifts a pant leg to show an ankle monitor. He has an immigration check-in next Thursday. He hopes he can have it removed then.

Wednesday, June 26

6:10 a.m. - A U.S. Border Patrol agent on a morning patrol spots a migrant woman’s body in a canal near Clint, Texas. It’s the ninth body discovered in a canal near El Paso since early June.

The El Paso County Sheriff’s Office later identifies the woman as 19-year-old Natividad Quinto Crisostomo of Paracho, Mexico, about 1,000 miles south.

In all, Border Patrol recorded five migrant deaths during the week of June 24-30 along the entire southwestern border. They include: A body found in the Rio Grande near Eagle Pass; a man who fell off a border fence near Nogales, Arizona; and a 43-year-old Salvadoran man who died while in custody. The federal agency doesn’t count bodies found by local law enforcement, a number that immigrant advocates say is much higher.

Other recent deaths, in addition to Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter Valeria, include three men found June 10 in a water tunnel near the border fence in El Paso and the bodies of a preschool-age girl and a man wearing a life jacket found in a canal the following day.

Migrants often swim across canals to reach the U.S. Some of the canals run parallel near the Rio Grande. Canal depths can reach 10 feet, with fast-moving water. The drownings picked up after water from local dams was released into the Rio Grande for the summer irrigation season.

9:17 a.m. - U.S. Border Patrol Agent Marcelino Medina stops his white Chevy Tahoe along a dirt road near Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park in Mission, Texas. He jumps out of the SUV and runs headlong into a stand of mesquite trees and brush. He’s joined by K-9 handler Agent Lorenzo Ochoa and Benicio, a 7-year-old Belgian Malinois.

Within minutes, they corral a group of migrants lying on the ground, trying to avoid detection. Their clothes are blotched with mud and scratches cover their arms and faces.

“¡Abajo!” Ochoa shouts. “¡Quédense abajo!” Stay down.

It’s been busy lately. The Rio Grande sector has nine processing stations designed to temporarily hold 3,363 migrants. Currently, nearly 8,000 are crammed into the stations. Roughly 1,000 more cross over from Mexico each day. “It’s a challenge,” Medina says.

Later, he encounters another group of 23 migrants along a path near the Rio Grande. Their clothes are splotched with fresh mud, their eyes weary. Most of them are women and small children. One woman is nine months pregnant, her due date four days away.

“Are you OK?” he asks them in Spanish. “Do you need water?” He turns to the pregnant woman: “Do you need help?” The woman, rubbing her belly, says she’s tired but fine.

As he’s processing them, another 13 migrants emerge from the brush, followed a few moments later by six more. Medina radios headquarters for more transport.

10:51 a.m. - An enlarged photograph of the bodies of Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and 2-year-old Valeria, the Salvadorans who drowned attempting to cross the Rio Grande earlier in the week, sits on an easel near the center of the Senate chambers in Washington, D.C.

Senate Democratic leader Charles Schumer stands behind a wooden desk in the chamber’s front row and gestures repeatedly at the poster-size photo.

“These are not drug dealers or vagrants or criminals,” he says. “They are people simply fleeing a horrible situation in their home country for a better life.”

Schumer says the deaths might have been prevented if father and daughter could have applied for asylum in the United States from their own country, as Democrats have proposed. Or if the U.S. provided foreign aid to stabilize the government in El Salvador. Or if U.S. ports were adequately staffed with asylum judges to hear the cases. “That is what is at stake,” he says.

A few hours later, Trump, on his way to an economic forum in Japan, is asked about the photo. “I hate it,” he says flatly.

He blames Democrats for not doing more to change immigration laws. “And then that father, who probably was this wonderful guy with his daughter, things like that wouldn’t happen,” Trump says.

1:03 p.m. - In Tapachula, Yulisa Almendarez, 26, makes tortillas by a wood fire as her son, 12-year-old Jose, kicks a soccer ball nearby with other children. Her daughter, 5-year-old Jasmine, clings to her mother, the child’s nose blistered with a skin infection.

The family has been at the Albergue Jesus El Buen Pastor shelter in Mexico for more than a month. Located on the outskirts of town, the shelter is long and narrow, with an open courtyard where children play soccer and adults sit under the shade of trees in the oppressive heat. Smoke gathers from the outdoor fireplace where women cook tortillas and pots of beans.

At night, adults sleep with their children in dormitory-like rooms packed with bunk beds – the men in one area, women in another. The small shelter is designed for 250 people. Lately, twice as many have jammed into it.

Almendarez left Honduras in May, hoping to reach the U.S. In September, her husband was shot and killed by street gangs as he walked to the store with their son to buy sodas, she says. They lived in a wood house with one room. She earned about 2,000 lempira a month, the equivalent of about $80, cleaning floors.

“There are a lot of problems,” she says of her home country.

Other migrants at the shelter wait in a long line to see a nurse. Some complain of sore throats and headaches. Others stand shivering with fevers.

Edwin Morales, 33, of Guatemala, says he was horrified to see the photo of Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and Valeria. But he says the graphic photo won’t dissuade him from continuing north.

“People are leaving to survive,” he says.

1:49 p.m. - Jose Mauricio Acosta Hernandez showers in an outdoor bathroom at Casa Tochan, a migrant shelter in Mexico City. He spent the morning juggling balls and bowling pins on street corners around the sprawling metropolis – a skill he learned from his uncle in his native Honduras.

Acosta Hernandez, 25, left Tegucigalpa in January with a U.S.-bound migrant caravan after he says gangs tried recruiting him to sell drugs. When they reached Mexico City, he and two other men pooled their money to buy bus tickets to Matamoros, across the border from Brownsville, Texas. They went straight to an international bridge. There, a Mexican immigration official told them they would have to wait up to a year to see a U.S. official.

After four days, they returned to Mexico City.

Now, he works to earn enough money to get his mother here. Today, he made about $3 from juggling.

3 p.m. - Border Patrol officials lead a group of journalists through their temporary processing center in Clint, Texas. Earlier in the month, a team of lawyers went to the immigration facility and described appalling conditions, including kids with vomit on their shirts and adults sleeping on concrete floors. The lawyers spoke with detainees who also reported spending 18 days locked up without seeing daylight, wearing the same clothes for days or weeks and having no access to a toothbrush or basic hygiene. Outbreaks of flu, scabies and chickenpox were common.

The station holds migrant children ranging from months-old infants to teen mothers.

On the media trip, children sit on the floor or on benches in a jail cell, closed off to the rest of the facility by heavy metal doors and windows. A group of boys plays soccer barefoot as the movie “Shrek” plays on a mounted television. Fans whirl overhead.

Nearby, boxes of disposable toothbrushes, baby bottles, lice-removal shampoo, pudding cups, Kool-Aid and Capri Sun drink pouches are stacked in a corner. Earlier this year, a Trump administration lawyer argued in a court proceeding that the U.S. government may not be required to provide toothbrushes and soap to immigrants during shorter stays.

Thursday, June 27

7 a.m. - The crowd at the El Chaparral port of entry, which connects Mexico to San Diego County, hushes as a worker emerges from the building with a megaphone and starts calling out names.

Luis Hernandez, 32, and his three sons, ages 5, 9 and 13, strain to hear.

Hernandez and his sons left their home in the state of Guerrero in southwest Mexico this year shortly after his brother, Rafael, was killed by a gang. In his phone, Hernandez carries a photo from a newspaper article showing his brother’s body, a bandage covering the spot where a 9-millimeter bullet pierced his head.

Hernandez says he fears he’ll be targeted next in Mexico. But Tijuana hasn’t been much better. He hasn’t enrolled the kids in school because he’s afraid they’ll be kidnapped. He’s afraid to leave them, so he doesn’t work.

"I didn’t want to be here," Hernandez says, "but the situation pushed me to come here."

While people wait, volunteers with a local legal aid organization pass out fliers in Spanish and French.

"Avena," a man offers, as he gives out cups filled with oatmeal, milk, water and spices.

The worker with the megaphone continues barking out names. Finally: “Hernandez!” It’s the last name he calls.

Hernandez is ready with a backpack and a small bag on wheels. The boys all wore hooded sweatshirts, cocooning themselves from the cool weather and overcast skies, while their father was dressed more formally, in a blue button-down shirt tucked into gray pants.

He and his three sons join about a dozen other people. Their life in the U.S. is about to begin.

10:23 a.m. - In Texas, Delmy López smooths her daughter’s hair and cleans her face with a wipe. It’s been six days since López and 2-year-old Perla arrived at the San Antonio Migrant Resource Center after crossing the Rio Grande.

She arrived at the river in the middle of the night as a storm raged. She propped Perla on her shoulders and forged across, the river’s swirling water nearly coming up to her chin. They reached a small island in the river. During a flash of lightning, she says, she noticed alligators on the opposite bank. She froze, terrified. After a while, a Border Patrol boat rescued them and agents took them to a holding facility, drenched and barefoot. The river had sucked off their shoes.

At the shelter, López waits to hear from her brother-in-law in San Diego about the next steps. Her future is fuzzy but, she hopes, brighter than her past.

12:18 p.m. - Syed Ashraf, owner of the Mimbres Food Mart in Deming, New Mexico, checks on the blue benches he’s set up outside the food mart, which doubles as a Greyhound bus stop used by migrants.

On Mother’s Day this year, federal agents dropped off 250 migrants outside the food mart’s doors. Some local residents dropped off supplies and snacks for the migrants. Others have criticized Asharf, accusing him of helping criminal groups that bring migrants to the U.S.

Asharf says he is sympathetic to the migrants’ plight. A native of Pakistan, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen in the mid-1980s and worked as a busboy and gas station attendant in New York City. Today, he owns businesses in El Paso, Deming and Las Cruces, New Mexico, which he’s used to put two children through college.

Given the chance, many of the migrants passing through Deming could reach similar heights, Asharf says.

“This is a generous country,” he says. “This is where I was able to accomplish all my dreams.”

2:40 p.m. - Border Patrol officials lead a group of 14 reporters through the Central Processing Center in McAllen, Texas. The center is designed to temporarily hold 1,500 migrants. Lately, it’s been crammed with about 2,400 people, including 400 children.

In one chain-link holding cell, about 100 men are squeezed inside, covering themselves in Mylar blankets. In another, men and small children huddle together. Bodies take up nearly every inch of the floor. Women are kept in separate chain-link cell on the other side of the cavernous room. Overhead lights are kept on all night, so agents can keep an eye on the migrants.

Carmen Qualia, a Border Patrol official who oversees the center, says the agents there are doing the best they can with the resources they have. But the sheer numbers of migrants streaming into the area and a lack of appropriate federal funding has strained the facility to its max, she says.

Repeated requests for more funding have not been fulfilled, Qualia says.

“This is way more than we ever anticipated,” she says.

Earlier in the week, U.S. Border Patrol chief Carla Provost toured a stretch of border barrier near Yuma, Arizona, and told reporters her agency faced a daunting task housing record numbers of young migrants.

"My agents are dealing with this the best they can," she said.

5:03 p.m. - Cristina Roblero, 33, waits for customers behind the counter of her small store in San Antonio, Guatemala, a rural town about 170 miles northwest of Guatemala City.

She has three children under the age of 10, four cows, a pig and a small hillside farm that grows potatoes and corn.

Roblero has run the store ever since her husband left for the U.S. six months ago to find work. Most mornings she wakes up before dawn to slaughter and clean chickens to sell at the store. She makes breakfast for the kids, tends the crops, feeds the livestock and cuts wood for their stove. Then, she tends the store and heads home around 8 p.m. to put the children to bed.

She earns about $56 a week, barely enough to survive on. She’d like to join her husband in the U.S., but the smugglers charge between $8,000 and $10,000 per person for the journey. If she sells everything she owns, including the four cows, she might get close. The rest she’ll borrow.

“I can’t make it here by myself,” Roblero says as she stands near shelves lined with bags of rice and bottles of cooking oil.

5:30 p.m. - U.S. Border Patrol Agent Jose Garibay speeds his SUV along a section of border fence near San Luis, Arizona, and stops suddenly when he spots four women, one of whom is pregnant and walking next to a 3-year-old.

They surrender immediately. The women speak no English – or Spanish. Garibay looks at their IDs. Romanian.

In 2018, people from 113 countries were apprehended along the southern border, according to Border Patrol. More than 8,000 apprehended were from India, more than 1,000 from Bangladesh and Brazil, and more than 250 from Romania.

As day turns to night, Garibay drives his SUV east. The radio crackles. A motion sensor was tripped several miles east in a desolate part of the border. Agents talk back and forth over the radio, trying to determine whether the alert was caused by a migrant, an animal or another agent driving through the area.

Garibay decides to check it out. He flicks on his headlights. Directly in front of him, two men crouch low on the U.S. side of the fence.

“Here we go,” he says.

Friday, June 28

4:38 a.m. - Waiting to enter the U.S., Hugo Aguirre naps in an old-model SUV under a streetlamp still aglow in the predawn darkness. On his way to his job at a metal recycling plant in El Paso, he’s parked in a line on the Mexican side of the international bridge connecting Juárez with El Paso that won’t start moving until 5 a.m.

Earlier this year, the Department of Homeland Security reassigned 700 customs officers to Border Patrol duties to help with the crush of undocumented migrants. That has tripled wait times for some border residents – U.S. citizens, legal residents and others – who cross each day from Juárez to jobs in El Paso.

Commuters who once arrived in the vehicle or pedestrian lines at 6 a.m. for their commute across the bridge now arrive at 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. to get to work on time.

“I know they are desperate,” Aguirre says of the migrants who have flooded his city. “If I have to wake up an hour earlier, so be it.”

10:30 a.m. - Rows of children stand and sing in the cafeteria at Dexter Middle School in Memphis, as parents record the scene on smartphones.

“I’m not giving up, I’m not giving up, giving up, no not me.

Even when nobody else believes

I’m not going down so easily.

So don’t give up on me.”

It’s the graduation ceremony for middle and high school students in the English as a Second Language (ESL) summer program for Shelby County Schools. The students, many from Central America, have been in the country less than a year. To many, learning songs in a new language was a challenge.

“They were afraid to sing two weeks ago,” music teacher Ed Murray says.

One student, 14-year-old Daniela Rivera, arrived nine months ago from Guatemala.

“We’re getting a good education so that we can help our country, as well as the United States,” she says in Spanish. She is learning English.

Her goal: Become a doctor.

10:52 a.m. - Catherine Gaffney labors up the side of a canyon in the Baboquivari Mountains in southern Arizona in 110-degree heat, dead grass crunching under her feet.

She pulls 4 gallons of water from a backpack and draws hearts and crosses on each in red ink. She places them underneath a small bush. “I try to find a little shade for them,” she says.

Gaffney has been dropping water in the Arizona desert for the past decade for No More Deaths, a Tucson-based group that provides water, food and first aid to migrants. The remains of more than 3,000 migrants have been found in southern Arizona since 2001, according to the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office. Many died of exposure and dehydration. Volunteers say thousands more have died but were never found.

In June 2017, Border Patrol agents raided one of the group’s camps to arrest four undocumented migrants receiving medical assistance. In January 2018, Justice Department attorneys won guilty verdicts against four No More Deaths volunteers on misdemeanor charges of entering a protected wildlife area without a permit and abandoning property – the water jugs they leave for migrants.

The Trump administration’s tactics toward the group trouble Gaffney. “It sends a message that the lives of those undocumented people don’t matter,” she says.

Earlier in the week along the same Arizona border, a different group camped along the Colorado River. Members of the AZ Patriots, a group of private citizens who banded together over the internet and try intercepting migrants as they cross the border, took turns patrolling stretches of the border fence, searching for migrants.

One morning, a group of four undocumented migrants – three adults and one child – crossed the river from Mexico and walked into view. Several AZ Patriots, including Paloma Zuniga, a Mexican-born naturalized U.S. citizen, chased them down.

“Go back! Go back!” Zuniga shouted at them. “This isn’t your country.” Later she boasted to her colleagues: “I pushed them. Somebody has to show them there’s some type of resistance.”

Not everyone agreed with that tactic. Mike Bennett of El Centro, California, who joined the group a few months ago, said that type of anger is misdirected.

“Why are you yelling at them? Have you walked in their shoes?” Bennett told Zuniga. “When you look in the kids’ eyes, that changes you.”

11:20 a.m. - Mike Furey makes his way up along a steel fence on the rocky slopes of Mount Cristo Rey outside El Paso. He acts as foreman of the structure, which he considers a wall. It was built with $8 million in private donations.

“I am doing this to support the American people,” he says. “Everybody is blocking the president. Nothing is getting done.”

The fence is part of a nationwide effort to erect a privately funded wall along the U.S.-Mexico border. As of this day in June, the “We Build The Wall” project had raised more than $26 million through a GoFundMe.com page started by U.S. war veteran Brian Kolfage and is led by a group that includes former Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach and former White House strategist Steve Bannon. Organizers couldn't say whether the barrier has deterred any significant numbers of migrants.

According to Furey, the average donation to the wall project is $67.

12:19 p.m. - Flanked by Homeland Security and Border Patrol flags in a conference room in Washington, D.C., acting Secretary of Homeland Security Kevin McAleenan defends his agency’s treatment of migrants.

“Contrary to the reporting, children at the border are receiving access to key supplies, including toothbrushes, appropriate meals, blankets, showers as soon as they can be provided, and medical screening,” McAleenan tells reporters.

Recent reports of unsanitary conditions at Border Patrol facilities sparked an onslaught of negative media coverage.

McAleenan says he has testified seven times to Congress since December, including five times since May 1, warning of overcrowded facilities. His pleas for urgent action included a March news conference at the border, where he said the situation had reached a breaking point with 14,000 migrants in custody, followed by another news conference in May as the number of detainees neared 20,000.

“All of this received relatively limited attention and little action until this past week on the Hill,” McAleenan says.

12:25 p.m. - Delmy López is in a Greyhound bus speeding west toward California. Her 2-year-old daughter, Perla, is next to her.

López’s back and hips still ache from carrying Perla across the churning Rio Grande the week before. She remembers the rawness on her scalp as Perla tugged her hair to keep from falling off her shoulders. When she closes her eyes, she still sees what she believes were alligators slipping their heavy bodies in and out of the water, and hears the clicking of their mouths.

She thumbs through Facebook on her phone and comes across a post about Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter, Valeria, the Salvadorans who died crossing the same river. This is not the tragic photo of the soaked, drowned bodies that was shared widely. This is a selfie, taken earlier. Father and daughter are smiling, seemingly full of joy and hope.

Questions gnaw at López: What if Martinez had carried Valeria on his shoulders, like she carried Perla, instead of inside his shirt? Did he stomp across the river instead of slide his feet? Why did God let her pass but take this family?

She stares a moment longer at the social media post, then presses “like,” attaching a tiny red heart to the image.

2:20 p.m. - Ruben Garcia sits at a long table, scrolling through the afternoon text messages.

“Sir, I have 2 pregnant females for non-detained appointments requesting placement,” reads one from a Border Patrol agent.

“Good morning, we have 80 for transport this morning, with up to 3 shuttle bus runs today,” another says.

Another one, from an ICE contact: “64 individuals. 1 Brazilian. Please advise.”

As director of Annunciation House in El Paso, a faith-based migrant shelter, Garcia has housed more than 100,000 migrants the past eight months – the most the 40-year-old nonprofit has ever seen.

Garcia recruited faith-based organizations in El Paso, New Mexico and Denver to help manage the overflow of migrants. In the spring, as the crisis intensified, he converted a former Costco warehouse into an emergency shelter, keeping the migrant crisis off the streets of El Paso.

As such, the city feels the migration crisis only when there is a sudden change, like each time the Trump administration redirects Customs and Border Protection officers from El Paso crossings to other points along the border, causing long delays at the international bridges.

“I think El Paso is very welcoming,” Garcia says. “Annunciation House took on the responsibility for all these refugees that otherwise would have fallen on the city.”

Saturday, June 29

2:56 a.m. - Having approved $4.6 billion in humanitarian aid for the border just the day before, Trump takes time from the G-20 Summit in Osaka to once again address the deaths of Óscar and Valeria Martínez. Trump argues that his proposed wall and tighter border security would have kept them alive.

“If they thought it was hard to get in, they wouldn’t be coming up,” he says. “So many lives would be saved.”

7:07 a.m. Tomas Gomez, of San Antonio, Guatemala, says he’s not a coyote, or smuggler. But he knows a lot about the business.

His hometown is a transit city for many migrants moving north. Each coyote has his own route and charges are based on the route’s degree of difficulty, Gomez says. Cheaper trips cost about $7,800 for adults. Children are an extra $3,200 each. The travel could take 10 days or longer.

For $11,000, migrants get food, lodging and transport by car all the way to the U.S. border. The fee includes the cost of bribing Mexican immigration authorities along the way, he says.

Trump has blamed smuggling organizations for the surge in migrant families arriving at the U.S. border, saying smugglers are capitalizing on migrants’ fears and exploiting them.

“People like to blame the guides, but the guides don’t go looking for people,” Gomez, 50, says. “It’s the people who are looking for guides.”

As Gomez speaks, his wife, dressed in a brightly colored dress worn by indigenous Mayan women, walks into the room. She carries a tray with coffee and a basket of sweet rolls wrapped in a hand-woven napkin.

8 a.m. - Maria Barrera walks into the General Abelardo L. Rodriguez International Airport in Tijuana with her son, Esvin Barrera, 16.

They carry one bag between them, filled with donated clothes they received at a migrant shelter in Tijuana. Barrera and her son traveled from Guatemala to the U.S. earlier this year in search of a better life. They entered the U.S. without authorization in Texas, spent more than a week in Border Patrol processing facilities in Texas and California, and then were sent to Tijuana under the Migrant Protection Protocols until their December court date.

But Barrera says she doesn’t want to wait indefinitely at a Tijuana shelter just for a judge to give them bad news. She says they were not fleeing death threats or persecution back home.

“They’re never going to give me papers,” she says, resigned to returning home to Guatemala. “It’s better if I leave.”

10:30 a.m. - Two-year-old Adriana holds her father's hand as they walk with her mom to a park.

They find a shady park near their new home in Long Branch, New Jersey. Adriana scrambles up a slide. On a nearby basketball court, players run through drills.

Just a few months ago, Jaime Escalante Galvez would wake each day in his home province of Jalapa, Guatemala, uncertain whether he would make it home alive. Guatemala’s homicide rate is 26 per 100,000 people – five times the rate in the U.S. and nearly three times that of Afghanistan, Peru and the Philippines, according to U.N. figures.

That was before he and his family decided to leave; before they squeezed under the border fence, arrived at a holding facility, then made their way to a church, then an airliner, then here, to a new life.

“I left my country. I left my belongings, my clothes. I came to the United States without anything,” Escalante says. “I was thinking about getting ahead. We migrated for a better life.”

He plays awhile longer with Adriana. Then, the family walks back home, where they are staying with relatives, stopping at a mini-mart on the way to pick up chicken drumsticks and rice for dinner.

1:39 p.m. - Henry Umaña struts down Mexico City’s expansive Paseo de la Reforma surrounded by rainbow-colored floats and flags during a gay pride parade. Crowds of people look on and cheer.

For Umaña, 33, it’s like walking through a dream. In his native Honduras, he lived in constant fear. Many of his friends were beaten for being gay. One of his partners was killed.

Since he emigrated two years ago, Mexico City had accepted him in ways he never imagined. Last year, he enrolled in a program that teaches software development to migrants. He now works with a tech startup in Mexico City making cellphones.

Umaña doesn’t know if he’ll be able to stay in Mexico. He applied for asylum in Mexico as soon as he arrived two years ago, but the country’s refugee office has denied his application twice.

“I jokingly told them, ‘So do I have to show up with open bullet wounds?’ They told me, ‘Yes, to have a better case, you need to have had something really bad happen to you,’ ” he says. “I told them, I’d rather try it now and stay alive then wait to get killed.”

2:21 p.m. - Yenelin Guadalupe García Solval sits in the shade of an apartment building in Anaheim, California, and sketches a portrait of her friend on her phone screen.

García Solval, 19, was recently granted asylum after a judge decided her persecution for being a lesbian in Guatemala warranted it. Her younger brother, Elvis, however, is still at risk of being deported. Attorneys for Elvis, 14, are filing a new case to try to get him asylum based on his age. If he gets returned to Guatemala, there’s nowhere there he could go – most of his family has left the country, García Solval says. Also, Elvis is at an age where street gangs there will likely try to recruit him.

Concerns for her brother aside, García Solval is optimistic for her life in the U.S. She’s captivated by detective TV shows. Upon graduating from Katella High School in Anaheim, she plans to study criminology in college and, someday, become a police detective.

“I feel like this is my real life. I belong here,” she says.

5:33 p.m. - After a harrowing journey from Honduras, Delmy López pulls into the San Diego bus station with her 2-year-old daughter, Perla.

She pumps her fist. “Me, here, in the United States,” she says, shaking her head in disbelief. She gathers her child and walks into their strange, new city.

As she waits for her brother-in-law to arrive to pick her up, López notices a homeless encampment across the street from the bus station. Tarps stretch across weathered lawn chairs and a battered shopping cart. Bundled-up men circle the area slowly.

“Why are they doing that,” she asks, “if the country is so rich?”

Video: Despair and hunger at shelters in Tijuana

Photo Gallery: Growing up in a shelter: Migrant children face early years of instability

Video: A Texas border town is trying to help

Photo Gallery: Guatemala's western highlands: Fleeing poverty, corruption and poppies

Video: Immigration judges are drowning in caseloads

Photo Gallery: Migrants Delmy and Perla López cross the country on a Greyhound bus

Video: Congresswoman on immigration: ‘Maybe that’s one of the reasons I’m here.’

Photo Gallery: Fleeing Guatemala, migrant family travels to find new home in New Jersey

Video: Applying for asylum in Tapachula

Photo Gallery: As migrant crisis rages on, attention heightens on both sides of the border

Video: A woman’s unforgiving choice: Pay a smuggler $10,000 or stay in Guatemala

Photo Gallery: Seeking asylum, migrants share their shocking stories in LA immigration court

Video: The uncertain journey continues

Video: Migrants in Memphis build for the future

Video: ‘They're people just like us.’

Sunday, June 30

9:30 a.m. - In downtown El Paso, Elsa Aramvide unfastens the lock on a roll-up door and tugs it up to reveal Sunrise Wigs, a cornucopia of fantasy wigs, false eyelashes and clawlike acrylic nails. Wigs in red, blond and brunette and hair extensions in all lengths, shapes and colors decorate the walls.

The Trump administration’s decision to pull U.S. customs officers from their posts at ports of entry in El Paso has drastically affected wait times to cross into the city. Multiple vehicle lanes on the international bridges now read "cerrado" – closed – at all hours in glowing red letters; inside the port customs buildings, many of the barstool seats where CBP officers welcome pedestrian crossers sit empty.

Aramvide and her mother, Raquel Ángeles, say many of their customers have all but given up trying to cross the international bridge that for decades has delivered Mexican shoppers to the El Paso street vendors who cater to them.

“Our sales are 40% of what they were a year ago,” Ángeles said. “This street is deserted! It looks like an abandoned city. It makes us so sad.”

10 a.m. - A woman passes out programs for Sunday service at El Redentor, a mostly Guatemalan Methodist church in Memphis. Printed inside each program: the jarring photo of Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and Valeria, the drowned Salvadoran father and daughter.

“We pray for the fathers and mothers, sons and daughters who are coming, risking their lives in search of a better life,” the accompanying text reads.

Pastor Luz Campos, who was born in Peru, tells the 40 or so congregants not to forget their roots and to help recently arrived migrants. Some Memphis migrants, she says, are so afraid of immigration officials they won’t leave their homes. One woman is five months pregnant and won’t go to the hospital.

This is your new ministry, she tells those gathered: Outreach to these shut-ins.

“We’re brave!” she shouts. “How many say, ‘Amen?’ ”

“Amen!” the audience responds.

10:10 a.m. - In Mexico City, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador stands on the bed of a white pickup truck emblazoned with the insignia of the newly minted National Guard.

Flanked by his top military and police commanders, the president, known by his initials AMLO, rides past rows of hundreds of men and women standing guard at the large grassy field. An enormous Mexican flag casts a long shadow among them.

Since June, guard members have become the country’s de facto border patrol.

“We have to act, with the moderate use of force but respecting human rights,” the president tells them.

Around 3 miles away, hundreds of men and women march on Paseo de la Reforma and demand the president’s resignation. Since taking office last year, López Obrador has been criticized for being overly sympathetic with migrants.

“He’s giving financial help to people that are not from our country, when there’s so much need in Mexico,” says protester Olivia Quintero Bernal, voicing one of the key grievances against the president.

1:30 p.m. - It’s bright and warm in San Diego, and Delmy López plays with her 2-year-old daughter, Perla, at a playground in Balboa Park. Both wear new clothes, courtesy of López’s brother-in-law, Carlos Aldana.

But López is questioning how much longer their new life in the U.S. will last.

The night before, a motel clerk refused to rent her a room because she lacked proper ID (a U.S. immigration official confiscated her Honduran ID while she was processed at the border, she says). And a woman who was going to rent her an apartment suddenly withdrew the offer. No explanation given.

Aldana can’t afford to bring them into his house, so López is running out of options. She says she may try to find something in San Antonio, Texas, after an initial immigration hearing. If she can’t find a shelter there or in San Diego, she may have to return to Honduras.

“It seems,” she says, “my dream is about to end.”

5:02 p.m. - Waldina Bonilla Rodriguez, 32, keeps an eye on her 8-year-old son, Oscar, as he weaves through the crowds in central Tapachula, Mexico. He’s barefoot and begging for money.

Rodriguez holds out a small plastic cup while her 2-year-old daughter, Delin Nicol, tugs at her tank top. Every few minutes, she rattles the few coins in her cup, hoping for a few more.

Rodriguez arrived here in mid-April after fleeing her home in Honduras. The family spent the first two weeks sleeping on the ground in a park in the center of the city. For the past two months, they’ve been living in a hostel with other migrants.

Gangs in her home state of Yoro, Honduras, demanded a weekly “tax,” pushing her deeper into poverty. Then, her oldest son, 9 at the time, was raped by a relative, Rodriquez says. She turned the man in to police. She pulls up a news article on her cellphone that she says proves her story. The relative spent time in jail but was released, she says. Rodriguez now fears for her life.

She has applied for asylum in Mexico but says it’s unsafe for them here, too. Her goal is to reach the U.S., where she hears migrants fleeing violence are welcome.

“I have suffered a lot of abuse in Honduras,” she says. “I don’t want my kids to suffer the same.”

The journey ends: The funeral of Óscar and Valeria

Dark-dressed men, women and children stream into the Municipal Funeral Home at La Bermeja cemetery in San Salvador. Inside are caskets containing the bodies of Óscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter, Valeria.

They left El Salvador in April, along with Martinez’s wife, Tania Vanessa Ávalos. Martinez dreamed of finding work and buying a house where Valeria could grow up.

The funeral draws more than 200 people, including friends, family and church members. The mayor of San Salvador and president of El Salvador send flowers.

The next morning, two caskets are lowered into the ground at La Bermeja. The family ceremony is private, so the throngs of reporters and rows of TV cameras wait just outside the gates, where the white arch of the cemetery wall reaches upward into an almost cloudless sky.

The funeral makes international headlines.

More than 2,000 miles away, along the U.S.-Mexico border, other stories and deaths unfold without notice.

More in this series

What happens to migrant children detained by the US government? One immigrant's story

How the USA TODAY Network spent a week reporting on the border to learn more about migrants

More migrants arrive from Guatemala than anywhere else. A dangerous flower is partly to blame

Local governments spend millions caring for migrants dumped by Trump's Border Patrol

US border crisis: Who are the migrants, why are they coming and where are they from?

Under surveillance: The lives of asylum-seekers and undocumented immigrants in the US

Is President Trump provoking illegal immigration by cutting aid to Central America?