For 15 years or so, northern Lebanon’s lively, working-class neighbourhood of Jabal Beddawi has been a place where people go to escape war.

But it’s a community that may not last. Lebanese politicians are pressing for the mass return of the country’s estimated one and a half million Syrian refugees – voluntarily, or otherwise.

What was once a grassy hill scattered with olive trees and small plots of chickpeas and beans has become a thriving and chaotic multicultural neighbourhood of as many as 60,000 people: Lebanese escaping Israeli airstrikes in 2006; Palestinians fleeing clashes between an extremist group and the Lebanese Army that destroyed their refugee camp the following year; then Syrians crossing the border and settling in the area around 2012, as war engulfed much of their country.

In Jabal Beddawi, which sits next to a separate Palestinian refugee camp, poverty is widespread. Up to half of all children are out of school. Jobs are scarce. Rents have skyrocketed. Healthcare is inadequate or expensive. Domestic violence and young marriages are not uncommon. And dissatisfaction – with government incompetence and alleged corruption, byzantine international aid programmes, and the seeming impossibility of securing a visa to travel to Europe, Australia, Canada, Turkey, or anywhere seen as better – is endemic.

In other parts of Lebanon, these conditions, combined with nationalistic and sectarian tensions stoked by politicians, have resulted in crackdowns against Syrian refugees: curfews, evictions, even vigilante-style attacks.

Jabal Beddawi has largely withstood these types of divisions. While there has been occasional violence, the relationships forged by Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian neighbours have made a seemingly untenable situation liveable – sometimes even joyful.

At no other time of the year is the daily resistance — to hatred, austerity, and exile — more evident than over Ramadan: the Muslim holy month that ended this week and during which daily fasting transforms, each night at sunset, into collective feasts.

The New Humanitarian spent the majority of the month in Jabal Beddawi, chronicling the lives, relationships, and meals on one block that – at the heart of the global refugee crisis – has opted for community over division.

This is the story of four nights, in four Jabal Beddawi homes, this Ramadan….

At home with Naima Nasser, from Aleppo

To the south, Israeli planes are bombing Gaza. To the north, the Syrian government is dropping bombs over Idlib. In Lebanon, the stock market has been closed all day: public sector workers striking against proposed austerity measures.

But all across Jabal Beddawi, final preparations for the first night of the holiday are underway. Women ease trays of baked chicken out of their ovens. Men cluster around roadside coolers buying carob juice or clutching their receipts in the dessert shop, waiting for heaping platters of cheese-stuffed or pistachio-filled sweets.

In the home of Naima, who came to Lebanon from Aleppo eight years ago, a neighbour arrives a few minutes past seven, and hands over a plate of sheikh al-mahshi – aubergines stuffed with meat and boiled in a yogurt sauce. A sense of calm descends as dusk fills the streets and the evening prayer rings out.

“Eat! Eat!” Naima instructs her daughter Noor, handing the 23-year-old a plate of rice, kofta (spiced meatloaf), and a finely chopped tomato and cucumber salad.

Naima and her three daughters are among the thousands of Syrians to set down roots in Jabal Beddawi. They fled Aleppo after anti-government forces seized control of the eastern part of what was then Syria’s most populous city.

Noor sits upright on a stretcher tucked into the corner of her mother’s house, her broken leg covered by a blanket. A week before Ramadan she was hit by a car in a nearby town.

News of the accident rippled through Jabal Beddawi, where everyone knows Noor and her older sister Amani, who works at the mini-market that abuts their ground-floor apartment, which is made of plywood and tin sheeting.

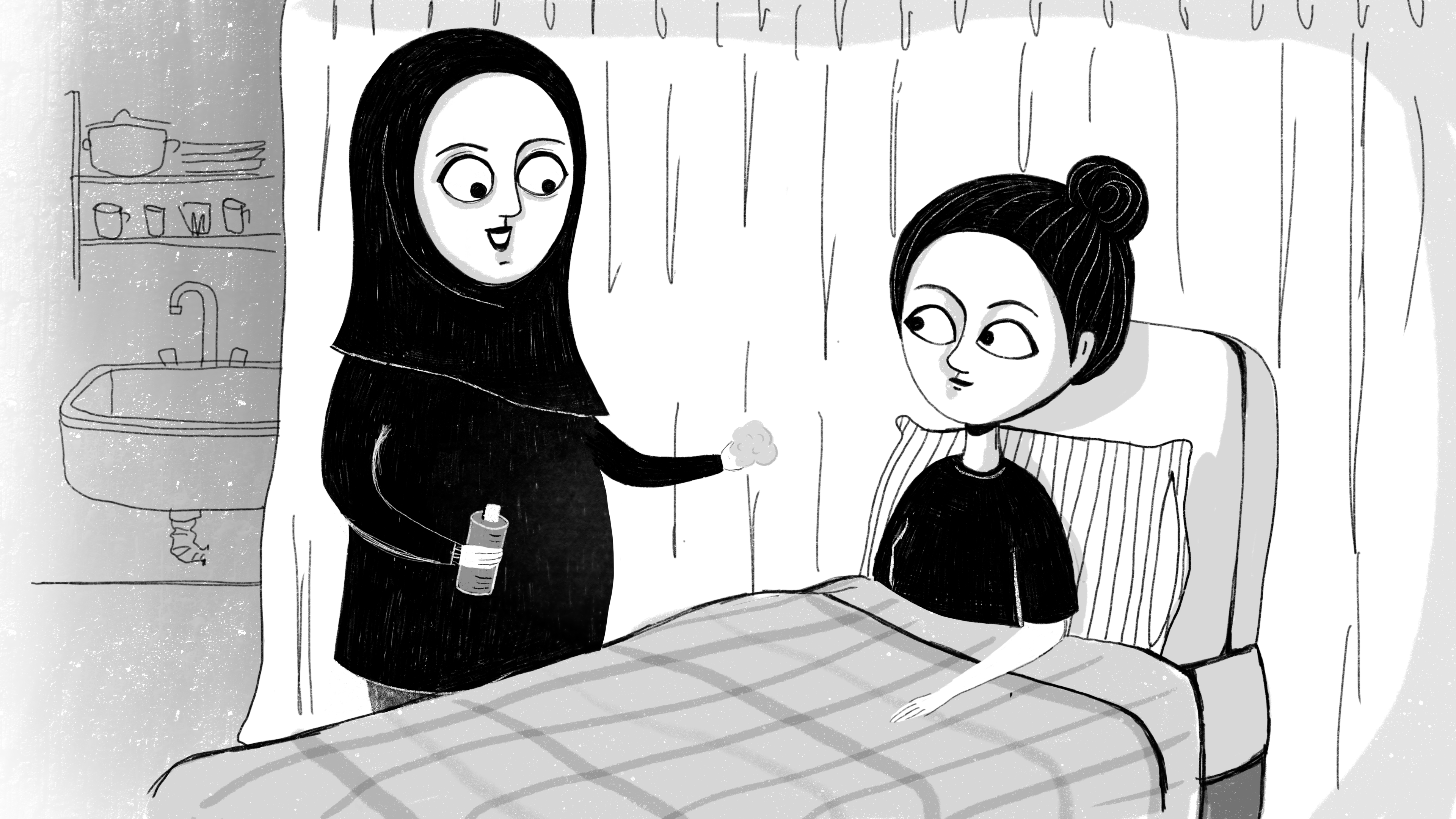

When she heard the news, Dalal, the Syrian Palestinian who runs the shop, asked her Lebanese neighbour Reem to watch the store while she rushed to the hospital.

In a neighbourhood ruled by gossip, the stories about Noor’s condition spiralled.

“Did you hear what happened to Amani’s sister?” a corn seller from Aleppo who is also called Noor asked his wife Ghazia the following night as she sat in the kitchen coring zucchinis in their apartment overlooking Dalal’s store.

Ghazia nodded without answering. She is desperately lonely in Lebanon; all her siblings have made it to Turkey, some even to Europe – but she is too afraid to put her shy young son on a boat across the deadly Mediterranean.

Now, even if she were willing, she couldn’t afford it: smuggling prices have reportedly surged from a few thousand dollars to up to $12,000 a person.

“The pretty girl, who just got married,” her husband continued. “I hear she broke everything: her leg, hips, her shoulder.”

A week later, Noor is home from the hospital after multiple surgeries, which were paid for by the driver who hit her. Her mother is now preoccupied with follow-up care, especially the risk of infection as her bandage has gotten dirty.

Naima and her three daughters live off Amani’s salary from the mini-market, which is only a few hundred dollars a month. Even for families with a higher income, decent healthcare is prohibitively expensive, for Lebanese and Syrians alike. Palestinian refugees receive healthcare through UNRWA, the UN’s agency for Palestine refugees, but many are also forced into the private system out of lack of specialists, funding shortages, or quality concerns.

Noor scrapes at the surface of her bandage.

“Don’t touch it!” her mother scolds, handing her a wet wipe.

She’s heard that a Palestinian woman who lives down the street used to work as a nurse; maybe she’d be willing to examine Noor’s leg.

Naima and her family are among the poorest on this block of Jabal Beddawi, but she says she still hopes to stay in Lebanon for the time-being: “At least everyone helps everyone else.”

At home with Dalal Alsalal, from Yarmouk camp, Syria

Dalal and her neighbour Samia’s Ramadan cooking routine began the way many things do in Jabal Beddawi: through WhatsApp voice messages. On the first night, while messaging after the evening meal, known as iftar, the neighbours realised they’d both prepared the same food: stuffed zucchini in yogurt sauce.

The second night, the same thing happened, only this time it was peas and rice. Tonight, the third day of Ramadan, Samia, who is from Aleppo, bought enough food for both of them and headed over to Dalal’s so they could cook together.

Dalal and her four children are Palestinians from Yarmouk. Over the last eight years, the refugee camp near Damascus has been seized by rebels, besieged by the Syrian army, taken by so-called Islamic State, and, last year, largely destroyed during the government’s capture of the camp.

Dalal and her kids fled Syria in 2013, shortly after her husband went out for bread one day and never came back. She remembers hearing the explosion that killed him. After six years, she feels like she’s made a new life in Lebanon, and would rather not have to start over a second time.

Her 15-year-old son, who works as an apprentice in a barber shop, is less keen on their new country. “I hate everything about Lebanon,” he says.

Dalal and her Syrian neighbour whip up a spread of fatteh (yogurt, chickpeas, and fried bread crisps topped with nuts), salad, kibbeh (bulgur, minced unions, and ground meat), noodle soup, rice, french fries, and baked chicken, which was hand-delivered by a young Lebanese man from the nearby butcher shop. He always saves Dalal the best cuts of meat; he’s known her since he was 13, when he helped her carry a gallon of olive oil up to her apartment.

When it’s nearly time to break the day’s fast, Samia gathers her half of the food and heads home, trailed by her eldest daughter, a rail-thin girl who lost weight during the siege of Aleppo and has stayed that way ever since.

“Are the other girls avoiding school too?” Dalal asks Sidra, her 16-year-old daughter, as they sit down to dinner. One of her classmates was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and Sidra is afraid of catching it.

Sidra is quiet and studious, and she spends her mornings in class and her afternoons in university entry exam classes. “If she scores well enough, maybe she can travel, attend a university in Europe, anywhere,” Dalal says with pride – although the course’s unpaid fees have been keeping her up at night.

Emigrating to Europe, Australia, or Canada is a common dream in Jabal Beddawi for Lebanese, Syrians, and Palestinians alike. But in recent years, as Western countries have sharply restricted immigration, legal emigration has become increasingly difficult and smuggling rates have surged. A small but increasing number of people have begun attempting to flee Lebanon by sea; during the first week of Ramadan, five Syrians went missing after their boat capsized off the coast about 10 miles south of Jabal Beddawi.

Dalal eats quickly and then hustles down the street to reopen the mini-market. As soon as she arrives, the children begin grabbing the store’s assorted fireworks: sparklers, firecrackers, bottle rockets, and roman candles. Unflustered, Dalal records each purchase in pencil in her notebook; she knows all the children and their parents, and she lets them buy on credit.

Although Dalal opened her shop less than a year ago, it has quickly transformed into a neighbourhood hub. Every night, she and other women sit outside on broken plastic chairs; Dalal plying her neighbours with cappuccinos and knowing looks as they divulge the day’s problems: debts, abusive husbands, burnt rice... Not everyone likes Dalal – she can be brash and she lets secrets slip every now and then – but everyone knows her, and she knows everything that happens on the block.

The street fills with the sour-egg smell of sulphur from the exploding fireworks and the scuffle of tiny sneakers. Amani’s youngest sister huddles in the shop’s entrance, shielding herself from the wind as she tries to light a firecracker. A man pushing a red-and-white-striped cart with beans and boiled corn calls out to Dalal: “The kibbeh was delicious!” Dalal has been preparing him a meal every night because he doesn’t have time to get home for iftar.

An older man slowly approaches the store, scowling as he shuffles closer. Two 11-year-old twin girls stroll by, arms interlocked, bickering about who is older and by how much. A child lights a bundle of steel wool on fire and whirls it through the air, sending golden sparks flying in all directions.

“It’s too much!” the older man complains, gesturing at the children. Dalal feigns innocence. What can she do? She’s just the shopkeeper. After he departs, she ducks into the store and emerges with more sparklers.

At home with Reem and Muhammad, from Lebanon and Yarmouk camp

“Ten minutes!” Muhammad announces to his eldest stepdaughter, Halima, in the kitchen of their apartment in the building adjacent to Dalal’s store. Halima glances at her phone, double-checking when it will be time for iftar. “Wow, it’s exactly 10 minutes,” she says.

She and her two younger sisters clearly look up to their stepfather, a lanky 27-year-old Palestinian man who likes martial arts and grew up in Yarmouk.

Halima’s mother, Reem, stirs pureéd tomatoes into a pot of Chinese-style chicken sizzling on the stovetop. A Lebanese woman who works as a French-language tutor, Reem is moving slowly. She’s been experiencing dizzy spells ever since realising she was pregnant.

“We can eat!” Muhammad declares.

After dinner, he and the girls devour a plate of qatayef, yeasted pancakes stuffed with clotted cream, while Reem helps two of her students with their homework. They are among a handful of children she tutors for free; their father died in Homs. Some nights her father gives his fidyah – a Ramadan donation made by those too sick or old to fast – to the girls.

Reem knows she could earn more by focusing only on students who can pay, and her family could certainly use the money. But she can’t turn kids away; it bothers her how many children in the neighborhood are out of school. Some work at their parents’ shops or restaurants, or sell tissues down on the highway. Other families can’t afford to pay the bus fees to school, which can add up to $15 a child each month.

A politician’s face flashes across the television behind the girls bent over their notebooks. “He hates Syrians,” Reem mutters. “He doesn’t want to allow us to pass along our [Lebanese] citizenship.”

Marriages like Reem and Muhammad’s are somewhat uncommon in Lebanon. There is a pervasive social stigma against Lebanese women marrying Syrian or Palestinian men, in part because Lebanese women cannot confer their nationality onto their children if their husbands are from elsewhere.

Over the last few weeks, Reem has been agonising over her unplanned pregnancy, knowing Lebanon’s nationality law means any child she has with Muhammed would be a Palestinian refugee, subjected to restricted access to jobs and be prohibited from owning property. “Sometimes I think about taking my daughters and just travelling somewhere, anywhere,” she says.

Instead, these concerns drive Reem to attempt an at-home abortion (her first name has been changed, because abortion is criminalised in Lebanon). Later, during the second week of Ramadan, she takes the abortion-inducing pills as Amani, Noor’s sister who works in Dalal’s shop, plies her with ginger tea and jokes to pass the time. But despite days of cramps and bleeding, Reem’s pregnancy continues – and she does not have hundreds of dollars for a clandestine surgical abortion.

At around one in the morning, Reem and Muhammad go for a walk, admiring the colourful lights strung across the balconies.

An unseasonably cold wind picks up, and Reem and her husband rush back toward their house. But first, they stop by to check on Noor.

“The bandage is still dirty….” says her mother. “Have you heard about a nurse, who lives down the street?”

“Don’t worry,” Reem says. “I’ll change the bandage tomorrow after iftar.”

At home with Nadia Aal and Bilal Abul Latif, from Lebanon

“Every day I work, and work, and work, and there’s still more work!” Nadia exclaims, shaking an unruly comforter flat onto her bed. Unfolded clothes sprawl across the living room. An overflowing laundry basket sits expectantly under the clothesline. Dozens of lemons wait to be squeezed.

Around the corner, her husband, Bilal, unloads boxes of carrots and dates from a truck and stacks them on the sidewalk in front of his juice stand. He has overhauled his falafel shop for the month of Ramadan, stocking it with two-litre bottles of carrot, orange, and liquorice juice. And he’s enlisted his wife’s help: she’s in charge of preparing the lemonade each day by hand.

“What time is it?” Nadia asks her daughter. “Six-fifteen?! I haven’t prayed yet, and I haven’t even started the food.”

But an hour later, inside the Lebanese family’s home everything is ready: fatteh, and rice, and molokhia – jute mallow with chicken – and sfeeha, meat pastries prepared by Nadia’s Palestinian friend, who temporarily relocated to Jabal Beddawi during fighting at the Nahr el-Bared Palestinian refugee camp in 2007 and now visits each night during Ramadan to attend mosque and visit friends.

After dinner and the evening prayer, the local tailor drops by, and Nadia orders her fast-growing 14-year-old son Zakaria to slip on his new jeans. “I don’t know why boys want their pants so tight these days,” Nadia says, as the tailor pins the inside leg.

After the measurements, Nadia and her children walk over to Dalal’s mini-market, where the shopkeeper has organised the children into a game of capture the flag using a small white towel. Nadia’s husband pulls up a few minutes later in his truck.

Bilal was shot in the leg a few years ago during the nearby fighting in Tabbaneh and Jabal Mohsen, when the politics of the Syrian war spilled over the Lebanese border and erupted in intermittent clashes between two impoverished Tripoli neighbourhoods, one largely Sunni, the other Alawite. Between 2011 and 2015, the sectarian gun battles and suicide bombings killed over 200 people and wounded many more, including Bilal.

Jabal Beddawi escaped this fitful war but isn’t immune from occasional violence. Later during Ramadan, Dalal was lucky not to be injured when she was caught in the crossfire of a shootout over money between a Lebanese family and a Palestinian one. Three people remain in the hospital, and the shooting inflamed the usually dormant communal tensions in the area.

Nadia visits Naima’s house, where she and her daughters Noor and Amani are smoking double-apple hookah, Amani’s favourite flavour. “It’s been forever since we’ve seen you!” Noor, who is just beginning to take her first steps with a walking aid, exclaims.

On their way home, Nadia and her family stop in front of their juice stand, where containers of sunflower oil, dates, pasta, marmalade, tomato paste, chickpeas, Lipton tea, tahini, and red lentils are piled onto the sidewalk.

Someone bought the food as a Ramadan gift for poor families in Jabal Beddawi, and Bilal and a friend bag up the goods to distribute the next day. “This month is blessed,” he says.

But it doesn’t feel that way for everyone in Jabal Beddawi, or in much of Lebanon, which has become increasingly inhospitable to refugees: authorities recently announced their intention to soon dismantle more than a dozen informal Syrian camps in another part of the country.

A retired teacher from Homs says he’s experienced little generosity from his neighbours in Jabal Beddawi and hopes to go back to Syria, where he remembers the streets were packed with people shopping and visiting neighbours every night of Ramadan. “In five years here, not a single Lebanese or Palestinian family has invited me for iftar,” he says bitterly.

He’s not the only one talking about return: Even as many Syrians fear the risk of arrest, imprisonment, and forced military conscription under President Bashar al-Assad’s rule, Lebanon’s government says more than 150,000 others have already headed home.

Ali Mekdadi, a coordinator with Basmet Amal, a local NGO that runs youth programmes and a job training centre in Jabal Beddawi, says he started noticing Syrian families were departing about six months ago. Activities at the centre used to “have 20 Syrian children, and then a few weeks later, half of them would be gone,” he says.

Later in the week, Bilal sat down for dinner with friends, Fatima and Amr, who had fled Homs. The situation there is beginning to improve, says Fatima, although prices have skyrocketed and there are serious concerns about what is happening to people who go back to government-controlled parts of the country.

Over dinner, both Fatima and her husband say they aren’t likely to return to Syria anytime soon. This doesn’t stop her from extending a hopeful invitation to Bilal, her Lebanese neighbour: “Maybe one day, you’ll come visit us in Syria?”

(TOP ILLUSTRATION: Neighbours chat outside Dalal Alsalal's shop in Jabal Beddawi, in northern Lebanon. Since it opened last year, the mini-market has become a neighbourhood hub.)

lg/as/ag