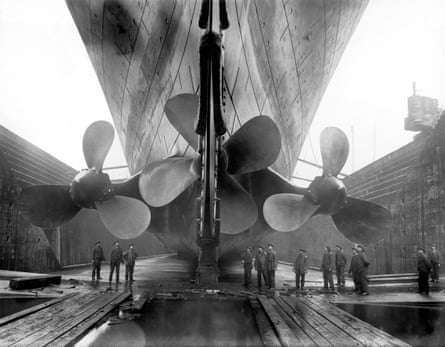

Until the recent advent of other kinds of vessel – vast tankers and container ships – ocean liners were the largest moving objects that humans had ever made. They were also very beautiful. How was it, then, that when the last great transatlantic liner was being built, only a few miles from where I lived, I never went to see it on the stocks? That my glimpses of it were always distant and accidental?

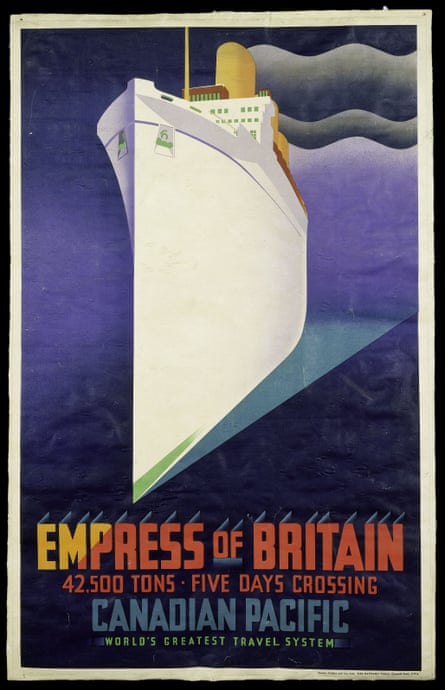

It was as though there was nothing exceptional about the sight of a steel hull and superstructure rising at a slant above the rooftops of Clydebank, the bow pointing inland towards the Dunbartonshire hills. Other famous liners had risen in the same way at the same place – the Lusitania, the Aquitania, the Empress of Britain and the two Queens – and smaller ships of the Canadian Pacific and Cunard fleets still regularly anchored downstream off Greenock to pick up passengers bound for Canada. By 1967 we must have known that jet aircraft were bringing these patterns of industry and travel to an end; even so, I was careless enough to be in a Glasgow dentist’s chair having a tooth pulled – personal decay at odds with a great historic moment – when the Clydebank hull at last slid into the river as the QE2.

That was also the year of the Sgt Pepper LP. History is more permeable and never as neatly divided as it likes to pretend: new bits flow into older bits. When the first Queen Elizabeth was launched, three decades earlier, for example, four-masted sailing barques still raced to Europe with grain from Australia. It takes time to discover what we shall miss or regret what we never saw, but some things, by being loved when they lived, stake their claim sooner than the rest. They include the sailing ship and the steam locomotive – and not least the ocean liner, which is celebrated in a magnificent exhibition that begins today at the V&A in London. It is a work of cooperation between that museum and the Peabody Essex, in Salem, Massachusetts; and it will move to the Scottish V&A in Dundee when that venue opens later this year.

Ocean Liners: Speed and Style is the first international exhibition devoted to the subject – a surprise, given that maritime disasters, onboard romances and the bright poster art of shipping companies have been part of popular culture for so long; that the very word “style” suggests the art deco interiors and cigarette-holder elegance of liners in their 1930s heyday, when rival British, French, German and Italian ships dashed across the Atlantic at average speeds of up to 31 knots (36mph) with their first-class cargoes of celebrated actors, society beauties and millionaires.

The exhibition gives this period its due with film clips, publicity material, branded crockery, haute couture dresses and surviving fragments of shipboard decoration. Onboard life could be adorable. What could be more captivating to a child than the child-sized ship’s wheel and engine-room telegraph made of teak and brass that the P&O ship Canberra installed in its nursery? What could be more tempting, to the child’s parents, than the sight of a lavish menu and the chance for a few days or weeks to pretend to be richer or better born, cut off by the ocean from feet-on-the-ground reality and people who might know better?“This is the life!” one imagines passengers telling each other over cocktails, with Southampton, New York or Cape Town still days away – though the exhibition is careful to remember the technology that made this possible, and the emigrants to the new world (1.4 million Europeans left for North America in 1913) on which the trade’s profits were originally founded.

Cramped in their steerage quarters, few of them could have found the experience attractive. And yet, far more than the stained-glass ceilings, libraries and string quartets on the upper decks, the ships on which the migrants sailed were in themselves beautiful, crafted and shaped both for speed and heavy seas. Two displays make this point vividly. A 22ft-long model of the Queen Elizabeth reveals how proud the liner’s owners were of its pleasing form: created in 1940 to stand in the window of Cunard’s Broadway offices, it was said to be the largest model ever built, just as the fully grown version was then the largest ship ever built. The size and the detail are breathtaking. Elsewhere in the show, an entire wall is given over to a rippling blue sea, crossed back and forth by a series of computer-generated liners trailing smoke from their funnels. This too is transfixing.

Of course, these judgments are highly subjective. My idea of a beautiful ship is one that has at least one round funnel, placed centrally and raked at the same angle as the two masts; a straight stem and a rounded stern; and the curve in the sides of the hull known as sheer. Few ships have been built to this pattern since the 1950s, but all through my childhood and adolescence they appeared at the local shipbreaking yard, tall-funnelled little liners of 10,000 to 20,000 tonnes that had been launched in the 1920s for the imperial routes to Canada, South Africa, India, Australia and the far east. Many were named, in the Cunard tradition, after provinces in the Roman empire: the Franconia, the Samaria and the Scythia – and the Mauretania, which was bigger than the rest, and had to wait for the highest of tides.

After the ships docked, the wives and neighbours of yard workers would go aboard and return down the gangways with cabin furniture that would find a good home. The lifeboats went next, to be followed by the masts, funnels and superstructure, until all the oxyacetylene torches had to feed on was the lower carcass, leaving the keel in the mud like the vertebrae of a fish. And so generation after generation of handsome ships were wiped out – inevitably, of course: steel rusts, engines wear out, technology changes. But growing up I began to see that if they had been paintings or small cathedrals, their going would have caused more of a fuss.

Ships are ugly now. Diesel engines need exhaust pipes rather than funnels. Straight lines of steel plate are cheaper to assemble than curved ones. Cruise liners are piled high with sea-facing cabins: the block-of-flats look – so that as many customers as possible have a good view. The QE2, built to cross the Atlantic in winter, was among the last of the big ships shaped by design traditions rooted in the late 19th century.

I eventually made up for my neglect of the QE2’s launch by sailing on it to New York 30 years later, a fine voyage I shall always count myself lucky to have made. Today the ship lies uselessly in Dubai. How good it would be to be sail around the corner of a Scottish sea loch and find it moored there as Scotland’s last great artefact, smoke rising from its funnel, ready to welcome you onboard.