On Christmas Eve 1941, most people would have been gathering together with their families, wrapping (modest) presents or attending church services. Not so for 19-year-old Joan Joslin, who instead was summoned to London by the Foreign Office for an interview.

“I met a very off-putting woman named Ms Moore who asked me all sorts of questions,” recalls the talkative veteran, now 95 and living in Essex. After a very short interview, Moore stuffed some papers into Joslin’s hands; it was a warrant to travel to a town called Bletchley.

“She told me: ‘You must go home and pack your case and leave at once. Don’t tell anyone where you are going. You can tell your mother you’re going to Bletchley but don’t tell her anything else.’”

Given the nature of their work, which involved cracking foreign military codes, this top-secret process was a typical way those selected to work at Bletchley Park, a mansion in Buckinghamshire, were enlisted. All were bound by oath to never speak about their roles.

It wasn’t until the mid-1970s, when wartime information became declassified, that people were allowed to talk about their time there. Still, when the war was ongoing, many were excited by the prospect of a new adventure. “I was very happy because I thought it sounded like it was going to be interesting,” says Joslin.

First, she was first placed in Hollerith school, in a separate building to Bletchley Park, where she spent six weeks learning how to adapt Hollerith accounting machines into code-breaking machines. She also taught members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service, also known as Wrens, how to work the devices.

Later, her role involved intercepting messages from Japanese aircraft and German naval vessels. “Sometimes we would solve them in a day, other times it would take weeks. We learnt all our swear words there,” she chuckles. “Messages contained awful words and naughty sayings.”

When successful, their codebreaking efforts could have a monumental impact on the war effort. The decoding of one message led to the location of the Scharnhorst, one of Germany’s most famous battleships, being revealed. Allied forces were then able to attack and defeat the ship in the Battle of the North Cape, off Norway.

Arriving at Bletchley from the Auxiliary Territorial Service aged just 18, Betty Webb spent four years at the codebreaking centre working in various roles,including intercepting German police messages, which revealed the beginning of the Holocaust with the killing of thousands of Jews on the eastern front, and paraphrasing decoded Japanese messages. Despite the importance of the messages, Webb admits she was unaware of the significance behind the complex codes.

“The messages were in groups of five letters or figures in Morse code – nothing was clear at all. Some dates appeared. It was total gibberish, but you had to register everything, so senior people could call on a date or message at any time. We knew very little of what was going on. We really were in the dark.”

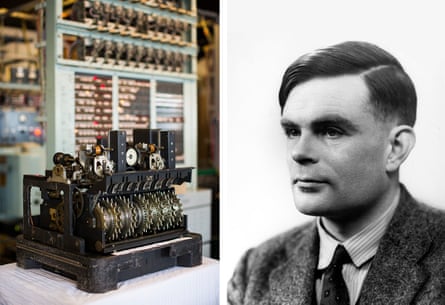

Joyce Aylard was stationed at Eastcote in London, where she operated the Bombe machine, designed by codebreaker Alan Turing to crack the Enigma code. Her role was to test different combinations to break the code. “These machines were very loud and noisy,” recalls Aylard, now 93 and living in Barnet. “I think I lost my hearing in my right ear from operating these bombes.”

When a code was broken, someone senior would come into the room and shout “job up”, she says. “So you’d stop and try another code. I was very pleased.” When the war in Europe finished, she was transferred to Bletchley Park, where she worked on cracking the Japanese code.

For Joslin, Bletchley ended up being more than just a place of work. She met Kenneth, her future husband, on her first day – although he didn’t leave a great first impression. “I arrived with another girl, who was blonde, and I was a brunette,” she recalls. “I heard him say to another engineer: ‘I’m going to have the blonde, you can have the dark one.’ I wasn’t impressed.”

But she worked with him for three years and the pair became great friends. “Suddenly, one day, it clicked,” she says. “He was really kind – he used to bring me a toffee every day.” Still, even though they were both working in the same room intercepting enemy secrets, they didn’t talk about their roles. “He didn’t know what I was doing, even though we were all working in an open room with each other. It was a closely guarded secret.”

Joslin also remembers Turing, the man Churchill credited with shortening the war by two years. “He was a very nice man, very shy,” she remembers. “We all used to have lunch at Bletchley on the green beside the lake, but he didn’t converse much with us. He was very eccentric. He used to do funny things like have a mug tied with a bit of string around his wrist, and because he had asthma, he used to wear a gas mask when he was cycling around on his old-fashioned bike.”

What saddens all of the women is that their families died without ever knowing what they achieved during the war. “Both sets of my family – my family and my husband’s – died without knowing, which makes me feel sad,” says Joslin. “I could never tell my mother anything.”

“My father was very upset that he didn’t know what I did,” adds Aylard.

As we wrap up our conversation, Joslin has one last story to share. She recalls when the war ended in 1945. She and her husband had been given leave, so they left to travel to Euston. “I’ll never forget the whole station was crowded with soldiers and I just wanted to shout: ‘The war’s over.’ And I couldn’t.”

Still, like all the women, she looks back at her time at Bletchley with the same overwhelming feeling of pride. “We all knew we were doing something good, and we all worked hard. There were no grumbles. We just got on with it.”

The German battleship Scharnhorst was incorrectly rendered as Scarnhorst in the original version of this article. This has now been corrected.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion