ZACATECAS, MEXICO — In a dirt-covered SUV with a cow’s skull on the hood and a wooden rack bearing the Valdez family name, Rafael, Joy, Maya and Catalina drive into the hills above a little town in the central Mexican state of Zacatecas.

It’s the kind of town known locally as a ranch. Cattle and men on horseback roam the streets. The Valdezes come here on weekends to find respite from the capital city, also called Zacatecas, and the larger questions of their lives.

Rafael, 41, wearing jeans and a cowboy hat, gets out of the SUV and looks with satisfaction across 7 acres of corn sprouts. Family history abounds on this farm, shared with his siblings and once owned by his grandfather. “I like it all year,” he says. “But this season is best, when things are growing.”

He left the planting this year to a brother, he explains on a summer afternoon. Any time now, he hopes, he might leave.

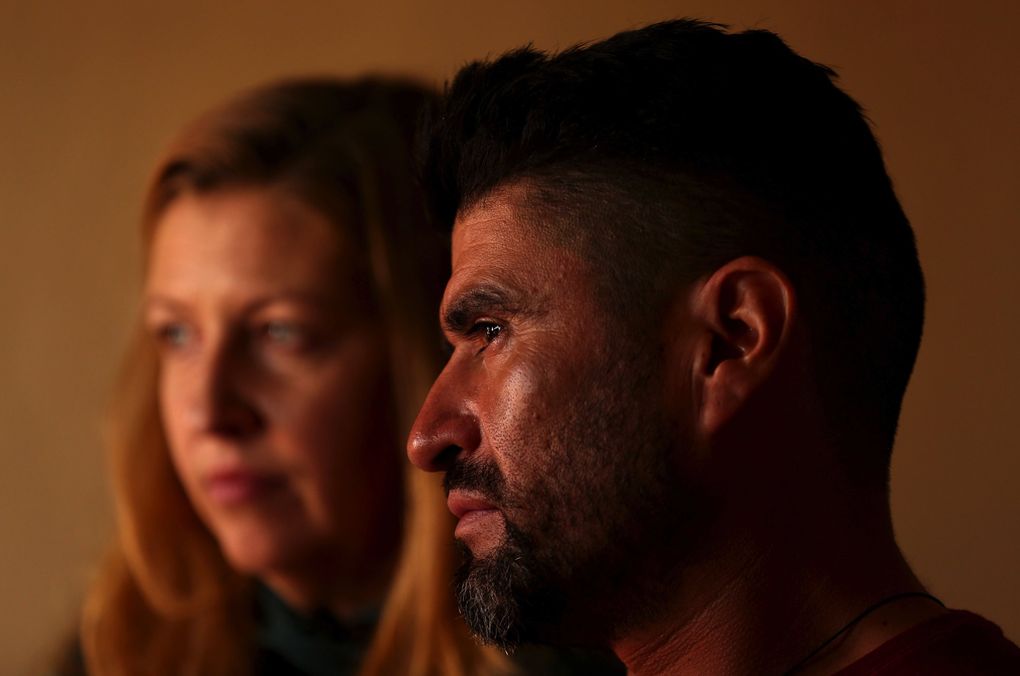

Deported from the Seattle area in 2013, with his American-born wife and children following later, Rafael has been trying to get the family back to the U.S. ever since. Just possibly, a door might open.

When we go back ….

If we go back ….

It’s the refrain in the Valdezes’ lives.

Deportees like Rafael may be rooted in Mexico. It may be a special place for them, and for their families. But so is the U.S., also home to a chapter of family history — and the future, as they see it.

There are simply more opportunities in the States, Rafael said, thinking of Maya, 11, and Catalina, 6. “I want to give them the best.”

As often reported in the U.S., deportation seems to have a finality about it: When people leave, they’re gone, and who knows what happens to them.

It’s not generally part of the immigration debate, reaching a fevered pitch under President Donald Trump as he seeks to ramp up deportations and wall off the border.

What’s apparent on the other side — past the usual stops for media and politicians at shelters and camps for migrants, deeper into Mexico where many deportees settle — is that the U.S. and its southern neighbor are deeply intertwined.

That’s especially true in places like Zacatecas, a state that has seen migration for more than a century. People who have lived in the U.S. are everywhere — running a cafe outside one of the local universities, leading passengers to planes at the airport, looking after cattle.

In Rafael’s hometown, a house is just as likely to be owned by someone living in Washington, California or Texas as by a local. There’s a lot of back and forth, often by people with legal status in the U.S.

And often not. Deportation is the most traumatic way to return to Mexico, but it’s hardly unusual.

While not everyone is determined to return to the States — “over here I feel more free,” said a 32-year-old who before being deported hadn’t lived in Mexico since he was 3 — many train their eyes northward with varying degrees of longing and desperation.

They also maintain a sincere belief they will go back, no matter that they were kicked out. In fact, they are usually eligible to apply again after a period of time. Some actively work at being ready, by keeping up their English, for instance. But it’s not always possible.

Deported in 2011, Rafael’s friend Chavo Eudave de la Torre has an 11-year-old daughter who lost most of her English despite spending the first six years of her life in South King County. That pains him, as does his inability in Mexico to provide for his daughter as well as he would like. He can’t afford a table for them to eat on.

The Valdezes are better off, although deportation has certainly cost them, with the girls struggling to fit in at school, Rafael worrying about how to protect his family against Mexico’s endemic violence and Joy doing her best to integrate into a world she doesn’t feel fully part of.

“I’m not sure where we belong. We’ve been gone for six years.” Joy said on the drive from the city. Tears fell, and she looked out the window. “Maybe it’s harder on me than I realize.”

On the roof, a bit of Seattle

The rooftop deck Rafael built onto the family’s house in the city is a shrine to the Seahawks. A huge mural, painted by Rafael, features the team’s logo, the Seattle skyline and a 12th Man flag flying atop the Space Needle.

Beyond the deck, houses with occasional splashes of color stretch to mineral-rich hills — mined by indigenous people even before the Spanish got here and built an industry. It’s a pretty view — but with too much concrete and rebar and not enough greenery for Joy’s taste. “I would like to put planters on the roof if we’re going to be here,” Joy said. “I can’t invest in that at the moment.”

She misses the gardens of Kirkland, where their house had well-tended front and back yards and space for a floral business Joy ran.

Although a comedown from that suburban lifestyle, theirs is not the grim existence some of Joy’s friends surely imagined when they got mad at her for taking the kids to Mexico because she insisted they needed their father.

The Valdezes occupy a compact, two-story house alongside teachers, shop owners and delivery drivers. Rafael helped pay for their house, formerly his mother’s, with money he sent from the U.S. while working up to three jobs as a chef, laborer and janitor.

Before moving to Mexico, Joy lucked out by getting a flight-attendant job for a U.S. airline. That doesn’t help their standard of living in Mexico, though, since the couple keep their dollars in the States to maintain their Kirkland house — now rented out. They survive mostly on what Rafael earns as a carpenter, working on and off so he can look after the kids when Joy is away. When in town, she runs a neighborhood shop selling dresses brought back from American thrift stores and Ross Dress for Less.

“I don’t think we’re poor like Mexico-standard poor,” she said. But money is tight, their furniture either hand-me-downs or made by Rafael. What middle-class trappings they have — washing machine, refrigerator, Kindles for the girls — come from Joy’s dad in Spokane, a pastor, who visits periodically.

“I was OK with being in Mexico someday,” Joy said, recalling the years after she and Rafael met, when he was 19 and she 21, working at an Indian restaurant in Kirkland. “I had been here. I thought it would be neat to have a farm and grow vegetables.”

That would be on their own terms.

A DUI conviction for Rafael, leading to deportation, brought them to Mexico under different circumstances. In the end, city living seemed more practical, in part because of Joy’s airline job.

Vivacious, with a decent command of Spanish, she comfortably navigates her neighborhood. She chimes in at a classroom meeting for moms about Father’s Day, and warmly greets customers at her store, allowing a regular to try on clothes at home.

Still, she said, “I’m isolated.” Outside her in-laws, whom she adores, she has no real friends.

Rafael, who moves with an easy self-assurance among people he knows, has warned her against striking up conversations with strangers. Organized crime runs rampant in Mexico. “You need to be on guard to defend your family,” he said.

It’s always there: a dark undercurrent beneath a surface of normality.

Living under threat

Zacatecas’ capital city attracts tourists. With 190,000 residents, it boasts museums, cafes and an elaborate, baroque cathedral. June is graduation season, and parties are everywhere. One night, a throng of people followed a band into the central square. Dancing broke out and people emptied mescal-filled jugs into miniature mugs hung around their necks.

A few nights later, masked police rode past the square atop a truck, armed with assault rifles.

Maya and Catalina’s school once sent a warning to parents: Kidnappers were disguising themselves as nuns and clowns.

The girls are not supposed to play outside unless their parents keep watch. “I’ve let up on that,” Joy said. “I don’t want my kids to grow up in a jail.”

Rafael remains wary. Joy has long blond hair that immediately brands her a foreigner — so much so that officers at a police checkpoint once couldn’t stop asking questions, including “why is she your wife?” Rafael says the girls, particularly light-haired Catalina, don’t look Mexican, either. And while fluent in Spanish, they use English with each other. That could make them targets, he said.

“I cannot say: ‘Don’t speak English,’ ” Rafael said. “It’s their mother tongue.”

In fact, he and Joy encourage the girls to practice, so they’re equipped to go back to the States. Joy stocks the house with English books and games. Rafael, needing to practice, too, also speaks English at home.

One spring day, Rafael went into his and Joy’s bedroom to draw up cost estimates for carpentry projects. Maya was taking a nap after school. Catalina was playing inside.

All of a sudden, it was too quiet. Rafael went to Catalina’s room to check on her. She wasn’t there. He climbed the stairs. Not there. “I started shaking,” he recalled. He walked outside screaming, “Catalina!”

He went back inside. “Maya, get up and help me find your sister.”

Catalina was in her bedroom closet, asleep among her toys.

Rafael had reason to fear. Six years ago, his brother was kidnapped.

Around 1 in the morning, armed men broke into Lorenzo’s house and took him away, blindfolded.

“I thought I would never come back,” said the 44-year-old, who owns a construction business.

After nine days, partly spent tied up on a mountainside, he was let go.

He told the story at a Father’s Day family picnic, on cactus-scattered property above a canyon, also once owned by his and Rafael’s grandfather. Lorenzo’s face, relaxed moments before, became strained. He said he was so shaken after his release that he moved with his family to the capital for three years.

He moved back but still worries someone will grab his wife or kids when they go to the store. “I need to stop thinking that way and come back to normal life,” he said.

As Rafael went through the U.S. immigration-court system, he said he was afraid of Mexico’s gang violence and asked for asylum.

“General conditions of criminal violence and civil unrest” are not grounds for asylum, an appeals board said, rejecting him.

Rafael had then been in the Seattle area for about 15 years. He and Joy were married, but he could still be deported thanks to a 1996 overhaul of immigration law. Marriage to an American is no longer an easy route to legal residency. Catalina was a baby, Maya 5 years old.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) caught up with him following his DUI conviction in 2009 — his second, the first 11 years earlier — which stemmed from a camping trip near Ellensburg with friends, beer-drinking lasting into the early hours of the morning, and an ill-advised decision to move a car to where they would land after floating down the Yakima River.

The appeals board gave him 30 days to leave the country. As the husband of a citizen, he could apply for legal status — but not for 10 years, a common stipulation for people who reentered the country after having been deported. Rafael did so in 2003, after going home to visit his sick grandfather and getting caught sneaking back into the U.S.

Two years later, on the advice of a new lawyer, Rafael presented himself at the San Ysidro border and asked again for asylum. The lawyer had accumulated testimonials about Lorenzo’s kidnapping and the violence in the area. Joy, Maya and Catalina waited in the car as Rafael was questioned.

“Daddy’s going to stay there,” the girls were told at a restaurant the night before.

Rafael was taken to a detention facility, where he spent a few months before being turned down.

At the same time, a silver lining emerged: His new deportation order carried only a five-year bar. His lawyer, Paul Cook, said there’s confusion about how that relates to the first order, but conceivably Rafael could apply next year, if not sooner.

Cook said the prosecutor who handled Rafael’s 2009 DUI case recently agreed to retroactively change the charge to reckless driving, a decision that now goes before a judge. The lawyer, who is trying to reopen Rafael’s immigration case, hopes this will help.

As Rafael flipped through documents from his case on a table in their house, Maya peered over his shoulder. “Daddy, they called you an alien.” He made a funny face and growled. “Yeah, I’m an alien.”

‘Lots of talent just goes’

Rafael’s mother, a seamstress, wanted him to go to college, like several of her six children.

He had other ideas. “I just want to go somewhere else and see what’s there.”

He walked for three days through the desert into Arizona, led by a coyote. “I knew it was wrong but it wasn’t like a big deal,” he said. Akin to trespassing, he thought.

So many others around him had done the same. Are you going? It’s the question that hangs in the air when you get to be about 15 or 16, observed Kathleen Tacelosky, a professor of Spanish at Lebanon Valley College, in Pennsylvania, who has lived in Zacatecas.

Raúl Delgado Wise, director of a development-studies program at the Autonomous University of Zacatecas, traces the tradition of migration in the state to the turn of the 20th century. Modernization hit the state’s silver and gold mines, among the largest in the world. Machines replaced people.

A “huge depopulation of the state” resulted, Delgado Wise said, with the newly unemployed seeking work in the U.S. With their knowledge of metals, they were the “perfect workers for building the railroads.”

You didn’t get many questions when you crossed the border in those days. Immigration law was just developing.

Generation followed generation. Using research based on Mexican and U.S. censuses, Delgado Wise estimates 450,000 people born in Zacatecas lived in the U.S. in 2010 — equaling almost a third the number of residents in the state that year.

The exodus created ghost towns, said Genaro Borrego Estrada, a onetime Zacatecas governor who went on to serve in the federal government. “It’s very sad, very painful. Lots of talent just goes.”

Other towns came to depend on remittances from the U.S. to survive, hampering the development of a still largely rural and poor state, according to Delgado Wise.

Rafael’s family followed the pattern. His great-grandfather worked in Texas, his grandfather in California, and his parents in California as well. His mother sewed in a factory making zippers, hems and pockets; his father worked with Rafael’s grandfather at a lumber mill.

Rafael, like all his siblings, was conceived in the U.S.

His mom returned to Mexico just before each birth, unaware that she was missing the chance to make the children U.S. citizens. It was the Vietnam War era. People told her if she had boys, the government would one day take them away, into the Army.

She drove back to California with each new baby until the last birth. His father came home for that one, and died in a car accident.

Rafael was 7, and his California childhood was over. The family stayed in Mexico.

As time went on, other family members continued to go to the U.S.: uncles, aunts, cousins. “He has more family there than I do,” Joy quipped.

One Sunday, he gave a tour of a cousin’s planned retirement house at the ranch to show off the dark-stained pine furniture he built for her. She lives in Texas.

As he came out, he saw an older couple parked in the street and stopped to say hello. They had just arrived in town a few days earlier, after living in the Seattle area for nearly 25 years.

Agustin Rogero Elias, 73, said he had worked in restaurants during that time, as a cook or dishwasher, but he couldn’t get jobs anymore because of his age, prompting the couple to return home.

They didn’t have an easy way to make a living here, either. Still, they said they were glad to be back. “This is our land,” Rogero Elias said.

A friend’s heartbreak, hope

Rafael’s friend Chavo comes from the same small town, but even after eight years back in Mexico, he thinks about the U.S. all the time. And so does his daughter, Arianna.

“Big houses. Pretty houses. Green grass,” said the 11-year-old one day after school, talking in Spanish and remembering South King County, where she was born.

None of that can be found in their Zacatecas city neighborhood, characterized by featureless apartment blocks, graffiti and occasional gunfire. This year, an 11-year-old was found dead on the street, raped, Chavo said. In June, he was locking his apartment door for the night at 8:30 or 9 p.m., though he would stop doing so over the next couple months, as Mexico’s newly created National Guard started coming around and making arrests.

His tile-floored living room is bare save for a refrigerator and two chairs. Despite a paralyzed arm from a car accident that limits his work prospects, the 38-year-old said he earned well in the States cleaning office buildings. Currently, he makes about $170 a month working in the kitchen of a steakhouse with white tablecloths and the hushed atmosphere of fine dining.

On this day, the water in their apartment cut out in the morning, due to unreliable pipes, and was likely to stay that way for days. They washed their hands with water kept in containers.

Yet Arianna seemed cheerful. She hugged her dad and cooked lunch — pasta and a sauce of blended tomatoes, onion, water and garlic — which they ate standing over the kitchen counter.

Still, Chavo says she tells him, “I want to go back,” meaning to the U.S., where her American mother lives. “That breaks my heart,” he said.

In Washington state, Chavo married a woman with mental-health and drug problems, as well as an extensive criminal record, according to court and Child Protective Services records. The marriage was volatile, as he described it, and led him to despair.

Chavo lost his janitorial job. He was subsequently caught delivering cocaine and pleaded guilty to a felony, bringing him to the attention of ICE.

He was deported in 2011, when Arianna was 3, and barred for 10 years from applying to come back.

“I feel like I’m losing my mind,” Chavo recalled. He had looked after Arianna until then, and worried about her without him. He called her almost daily and got the Mexican Consulate in Seattle involved.

Child-welfare workers worried, too, records show, indicating among other things that Arianna was spending time in unsafe locations, where she witnessed two drive-by shootings. She was also found, in a T-shirt and barefoot, on a chilly April day by sheriff’s deputies called to a Safeway parking lot to investigate a reported fight between Arianna’s mom and grandmother, according to the incident report.

Eventually, when she was 6, the state sent Arianna to her dad in Mexico.

“My baby,” he calls her.

Now, he and a woman he married after returning to Mexico have a baby on the way. The marriage faltered, and the couple are divorcing. One source of tension: Chavo’s focus on the U.S. His wife refused to go should the chance arise. She is happy with her life in Mexico, where she can see her parents every weekend.

He was willing to go with Arianna and leave his wife and new child behind if necessary. The baby, who would know no other life, would be fine, he reasoned. His wife would be a good mother and both sets of grandparents would be around.

Arianna belonged in the U.S., he said. “That’s her country.”

Misunderstood in school

Ramrod straight, arms swinging stiffly, Maya marched in a small group of students back and forth across her school’s sports court. They were practicing for their role in a weekly flag “guarding” ceremony next year. It’s a huge honor to be asked; the school’s top students are chosen.

It’s also an indication of how well Maya has fared compared to many children of deportees. The Mexican government estimates that a half-million children or more in Mexico are transplanted American citizens.

“They face discrimination. They are mistreated. They are misunderstood,” said Gema Mercado Sánchez, secretary of education for Zacatecas state.

Teachers don’t understand why some of these kids are so quiet, failing to realize these “transnational students,” as they are known here, may have a mediocre grasp of Spanish and big gaps in their knowledge of, say, Mexican history.

“No one talks about transnational students, not even Google,” said Evelyn Leyva Gómez. She plugged the term into an online search while trying to help her American-born daughters, Ellie, 9 and Tori, 11, after they arrived two years ago in Zacatecas, her home state. No results came up.

When she was a teenager in the U.S., Leyva Gómez said, a bilingual education teacher worked with her for hours after school every day. Here, there wasn’t even an English teacher at her girls’ school, so Leyva Gómez became one. At home, she reads to her daughters once a week from an array of English books, including DK’s “History of the World,” one of Tori’s favorites. Even so, Leyva Gómez said, her oldest daughter is “stuck between both languages.”

Tacelosky, the American academic, who has long studied children brought to Mexico from the U.S., was living in Zacatecas, interviewing families, when she was invited by Mercado Sánchez to develop a curriculum to train teachers.

The education secretary said she felt it was important to nurture these students, who have a lot to offer, including English-language skills. And there may soon be many more of them, she said, as the Trump administration ramps up deportations.

Maya and Catalina seem to have escaped these adjustment issues, when it comes to academics, likely because they came here so young. But socially, it’s another story. Kids here, like everywhere, can be mean to perceived outsiders — even though the girls are both Mexican and American citizens and a big sign on the sports court honors migrants, or at least their donations that built the structure through a government matching program.

Classmates have called the girls “gringas” and told them to go back to where they came from.

“I ignore them,” Maya says. “I know what the truth is.”

Catalina came home crying.

The 6-year-old, it seems to her mom, gets excluded more. The first-grader, expressive and quick to hug, resorted to finding her sister on the playground until a teacher told her to stop and find other kids to play with.

“I don’t want to assume it’s based on her appearance,” Joy said. “I don’t see another reason.”

“How do you make that go away?” she wondered. “Is it by not acknowledging it?”

The future harbors more questions. If the girls return to the U.S. — as they are entitled to do anytime — what would they face there?

Joy is working on getting Catalina to read in English. It’s a struggle, despite making flash cards to help. The 6-year-old is learning to read in Spanish. That takes practice, too.

After school one afternoon, Catalina sat on her mom’s lap and sounded out words to a Spanish version of “The Little Mermaid” — “La Sirenita.”

Another afternoon, she and Maya eagerly played an English-language word game called W-I-N-G-O, using dominoes with letters. Joy, joining in, seized teachable moments. “Do you know what sound this is?” she asked. “Do you remember this word?”

They were in Joy’s store, their usual hangout after school. Rafael was making a cabinet in his adjoining workshop, ranchera music playing in the background.

Familiar as this world is to them, the girls appear ready to leave it. “I would be super happy and excited,” Catalina said.

Joy and the girls visited Washington state last summer. They stopped by the Kirkland house to check on the garden and look through boxes of stored belongings: a “story-about-me” book Maya made in preschool, holiday wrapping paper, family pictures. Joy choked up seeing one photo of herself, pregnant, lying beside her mom, then ill with cancer and soon to die. They were looking together at an ultrasound.

Joy and her daughters also spent time with her dad on his sprawling property in Spokane.

“It smells so good,” Catalina said of American mornings, untainted by the garbage dumped sporadically on Zacatecas streets. “It smells like sugar.”

Still, there are things and people they would leave behind — many of them located at the ranch — should they move to the U.S.

One Saturday, Maya, tall and slender, got out of the car upon reaching the town and leapt balletically across a central garden, arms spread wide. While their parents stopped at a little store to buy food for lunch, she and Catalina ran over to different trees, claiming them as their “houses.”

At their dad’s childhood house, where the Valdezes stay when in town, Maya excitedly checked out the rooms using a “ghost meter” on her Kindle. Catalina helped her mom make scrambled eggs.

Later, the girls rode bikes and played in the backyard with cousins, 5 and 9, who arrived in the afternoon. The sound of an ice-cream truck brought the four kids running.

This is the precious part of being in Mexico, Joy says: the opportunity for Maya and Catalina to get to know their cousins.

When it was time to go back to the city, Catalina cried, unwilling to separate. Joy tore her away, promising to come back the next day.

Special thanks to Mexico-based producer Ulises Escamilla Haro.