Here’s how we’ll know when a COVID-19 vaccine is ready

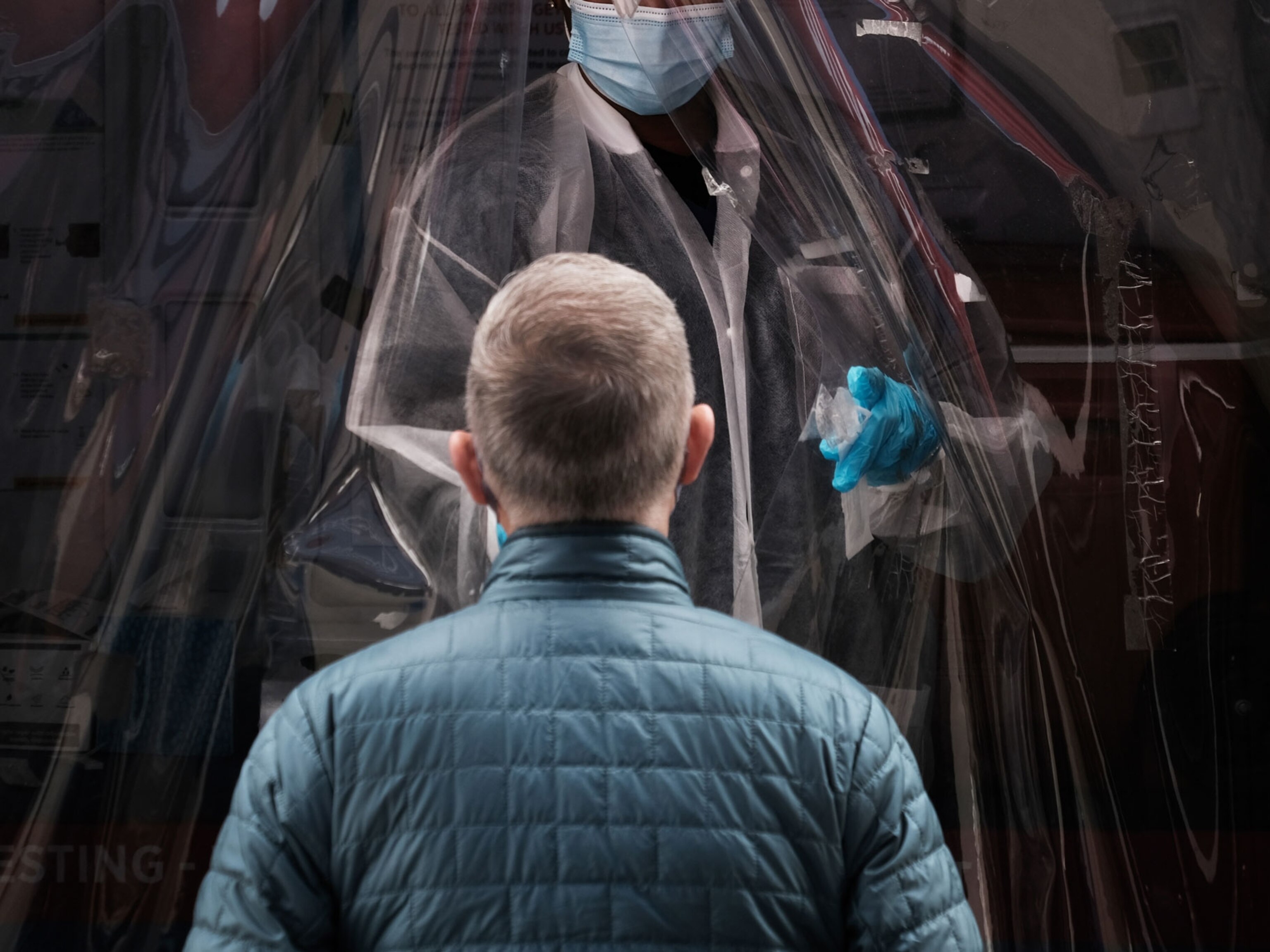

Health officials have set targets for how good and how safe a COVID-19 vaccine needs to be, but communicating that to the public can present challenges.

Private David Lewis was hiking with his platoon through the snow, despite feeling unwell from the flu. It was January 1976, and the 19-year-old Lewis was stationed in New Jersey’s Fort Dix, where about 230 other soldiers ultimately fell ill. But Lewis, who collapsed 13 miles into the training hike and succumbed soon afterward, was the only one to die. His passing sent the United States into panic mode.

The strain collected at Fort Dix appeared similar to the one behind the 1918 flu pandemic, and this connection made it big news. By the 1970s, high-risk groups were being urged to get flu shots—so the government immediately sought to tailor the vaccine against the Fort Dix strain, hoping 80 percent of the population would take it.

What followed was a debacle. The hastily-developed vaccine was linked to more than 500 cases of paralysis, and 25 people died from it. Soon after news of the Fort Dix outbreak first broke, half of the general public had voiced their intentions to get immunized. But as events unfolded, only 22 percent of the U.S. population ended up getting the vaccine by year’s end.

Now, as COVID-19 sweeps across the world and more than 140 vaccines are in the works to protect against it, the question is: How will we know when one is good enough and safe enough to counsel people to take it?

Although a typical vaccine can take years to get off the ground, those designed in this pandemic are moving ahead at a pace never seen before. At least one candidate, from the biotech company Moderna, is headed into phase three trials in July. In May, the U.S. government launched Operation Warp Speed, putting billions of dollars toward accelerating the design and testing of potential vaccines.

Some scientists are wary of settling on the first vaccine that comes to fruition. It’s a delicate balancing act for public health officials to decide when a vaccine is ready for mass rollout to the public.

For the COVID-19 vaccine, the ideal candidate would be able to establish immunity in at least 70 percent of the population.

If, for instance, they scale up production of a vaccine with limited effectiveness and promote it heavily, that might dissuade developers from striving to bring a better one to the market. “If you accept a vaccine with low efficacy, then you probably prevent the development of a vaccine with higher efficacy,” cautions Roland Sutter, who was coordinator for research, policy, product development, and containment for polio at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva, Switzerland, until retiring in December.

Parsing what makes a COVID-19 vaccine good enough for mass rollout is the primary challenge for scientists and policy makers in the coming months. They’ll also need to ensure appropriate safety checks—or risk repeating the mistakes of 1976 and losing public confidence.

Setting the goal posts

Vaccine development comes in stages, starting with phase one trials. These clinical trials generally assess the initial safety of a drug in a relatively small number of people; sometimes about 50 or so participants, although the number can vary widely.

Expanded phase two trials give an inkling of the vaccine’s efficacy. That’s often gauged by analyzing people’s blood to see if antibodies or other immunity sentinels are present that can neutralize the targeted pathogen.

Phase three trials try to better measure how well the vaccine protects people by scaling up to include thousands of participants and typically comparing the protection conferred to those who undergo immunization against those who receive a placebo.

But the real test, vaccine scientists say, comes when these preventative drugs are approved and given widely.

“A clinical trial is still quite a controlled environment,” says Charlie Weller, head of the vaccines program at Wellcome, a London-based biomedical research funder. People participating in the testing of a vaccine might be more conscientious about their actions and take fewer risks that might expose them to a virus because they are being followed by doctors. “You know you’re in a clinical trial when you’re in a clinical trial, and that might change your behavior,” she says. “So the real test for a vaccine is when it’s rolled out into a population.”

Even if they’ve advanced through these trials, some vaccines are simply more effective than others. (The reasons for this are not always clear. It may have to do with intrinsic factors of the virus being targeted—its propensity to mutate and how it propagates in the body—as well as how our immune system naturally interacts with it.)

Among vaccines known to be highly effective are the inactivated polio vaccine—a course of three doses of inactivated polio vaccine is virtually 100 percent effective against that disease—and the measles vaccine is roughly 96 percent effective after one dose.

Other immunizations are given even though they come with lower probabilities that they’ll protect against disease. Strains of the flu virus change from year to year, and this is part of the reason that receiving the annual vaccine against it will only reduce the risk of catching the virus by about 40 to 60 percent. The vaccine against malaria—known as RTS,S—cuts severe disease by only about a third, but it is still being explored as an option in hard-hit areas of the world. That’s because malaria often claims the lives of young children, and saving even a third of these youngsters translates into a tremendous gain, says Matthew Laurens, pediatric infectious disease specialist at the Center for Vaccine Development (CVD) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

For the COVID-19 vaccine, the ideal candidate would be able to establish immunity in at least 70 percent of the population, including the elderly, as outlined in April by the World Health Organization (WHO). On June 28, Anthony Fauci, director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said that he, too, would settle for a 70 to 75 percent effective vaccine.

On the flipside, the WHO says that the minimum acceptable would be a COVID-19 vaccine that was 50 percent effective. On June 30, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration mirrored this guidance, releasing a document that set the same baseline target. Some researchers aren’t convinced: “Fifty percent would be terrible,” says Byram Bridle, a viral immunologist at the University of Guelph’s Ontario Veterinary College in Canada. “For this pandemic to end, we need to achieve herd immunity,” says Bridle, and a vaccine only effective for 50 percent falls short of getting us to that goal.

Other scientists view any vaccine as only one part of a multifaceted approach to reducing the spread of the coronavirus, along with social distancing and wearing masks. “We have to look at the whole public health value of the vaccine,” Laurens says.

In a small clinical trial with the kinds of platforms that are being examined here for COVID-19, you rarely see severe reactions.Wayne Koff, Human Vaccines Project

Immunologists remain ever vigilant about the effects of new vaccines because there have been rare but noteworthy surprises in the past. For example, the first vaccine for diarrhea-causing rotavirus was withdrawn from the market in 1999 when it was linked to an uncommon and potentially fatal sliding of one part of the bowel into another. This severe adverse event wasn’t detected in the clinical trials leading up to its rollout. More recently, in 2009, the Pandemrix vaccine against the swine flu showed signs of a link to narcolepsy in Europe. (The vaccine was never licensed for use in the United States.)

“In a small clinical trial with the kinds of platforms that are being examined here for COVID-19, you rarely see severe reactions,” says Wayne Koff, president and CEO of the Human Vaccines Project, a public-private partnership that seeks to accelerate vaccine development. Adults and children receive millions of doses of approved vaccines each year across the world, and severe reactions are extremely rare.

In its phase one trials for the Moderna vaccine against COVID-19, four of 45 individuals who received the vaccine had a medically significant adverse reaction, including one man who developed a high fever and fainted. Yet researchers already knew that mRNA vaccines can sometimes overstimulate an immune system, and three of the four subjects who had these side effects were taking the highest dosage in the trial, which has now been discontinued.

Problems with public uptake

Assuming that a COVID-19 vaccine meets the WHO benchmarks, including that the “vaccine benefits outweigh safety risks,” an unknown share of the public still will need convincing to take the shot.

In May, a survey of more than a thousand people conducted by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that around 50 percent of respondents were certain they would take a COVID-19 vaccine when one becomes available. That’s about the same proportion that the center has found in the past when it asked about taking the flu vaccine, and it matches the findings of a Pew Research Center Poll conducted around the same time.

But there were a larger proportion of people not yet settled about getting immunized against COVID-19 than the flu: while 18 percent of those surveyed had said they were undecided about getting a flu shot, 31 percent said they had not made up their minds about whether they’d take a COVID-19 vaccine. Among those who say they might eschew a vaccine, twice as many people were worried about side effects from a COVID-19 vaccine as for one designed to prevent influenza.

Women are more likely to be unsure and be on the fence...it’s a potentially influential group.Jennifer Benz, The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research

The survey also revealed a curious divergence by gender. “Women are more likely to be unsure and be on the fence,” says Jennifer Benz, deputy director of The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Its survey found 56 percent of men said they would take the hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine, while only 43 percent of women said the same. “Women are oftentimes the healthcare decision makers in the household, so when you think about vaccinating the whole family and making healthcare decisions and appointments, it’s a potentially influential group,” Benz says.

The key challenge for the future, as Laurens sees it, is to explain to people how they can do their part in stopping the pandemic by getting immunized once a suitable vaccine is available. “We have to do our utmost to educate the public about how vaccines are tested and the safety profiles of vaccines and what they can actually do, and how they can prevent disease in a community,” he says.

Vaccine hesitancy might not be the only hurdle to overcome. Weller anticipates a scenario where—at least initially—public interest in obtaining the vaccine might outstrip the amount available.

Amesh Adalja of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore says that there might be “chaotic” scenes if demand is high and the rollout is not done carefully “Just think about Black Friday and what happens when people are in lines,” he says, referring to the shopping day after Thanksgiving when crowds may become impatient and overwhelm stores.

Coordinators of past immunization campaigns for other ailments are watching the COVID-19 vaccine development process closely, in hopes of heading off missteps that would undermine uptake and access. “It will not take much to discredit the vaccine in the eyes of the population,” Sutter says. “The rollout has to be carefully thought out so that it will not destroy confidence in the vaccine.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest