U.S. deaths from alcohol, drugs and suicide hit highest level since record-keeping began

Jayne O'Donnell

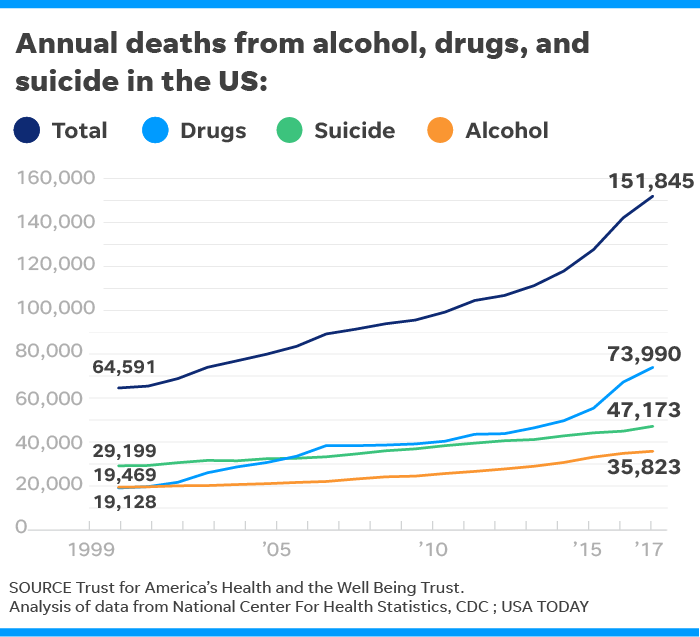

Jayne O'DonnellThe number of deaths from alcohol, drugs and suicide in 2017 hit the highest level since federal data collection started in 1999, according to an analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data by two public health nonprofits.

The national rate for deaths from alcohol, drugs and suicide rose from 43.9 to 46.6 deaths per 100,000 people in 2017, a 6 percent increase, the Trust for America's Health and the Well Being Trust reported Tuesday. That was a slower increase than in the previous two years, but it was greater than the 4 percent average annual increase since 1999.

Deaths from suicides rose from 13.9 to 14.5 deaths per 100,000, a 4 percent increase. That was double the average annual pace over the previous decade.

Start the day smarter:Get USA TODAY's Daily Briefing in your inbox

Suicide by suffocation increased 42 percent from 2008 to 2017. Suicide by firearm increased 22 percent in that time.

Psychologist Benjamin Miller, chief strategy officer of the Well Being Trust, says broader efforts are needed to address the underlying causes of alcohol and drug use and suicide.

"It's almost a joke how simple we're trying to make these issues," he says. "We're not changing direction, and it's getting worse."

The health and well-being trusts propose approaches including:

► More funding and support for programs that reduce risk factors and promote resilience in children, families and communities. Trauma and adverse childhood experiences such as incarcerated parents or exposure to domestic violence increase the risk of drug and alcohol abuse and suicide.

► Policies that limit people's access to the means of suicide, such as the safe storage of medications and firearms, and responsible opioid prescribing practices.

► More resources for programs that reduce the risk of addiction and overdose, especially in areas and among people most affected, and equal access to such services.

While overdose antidotes and treatment for opioid use disorder are needed, Miller says, "it's not going to fix" the underlying problems that lead people to end their lives, whether or not it's intentional.

In most states, deaths from alcohol, drugs and suicides increased in 2017. In five – Massachusetts, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah and Wyoming – those deaths fell.

Deaths from synthetic opioids, including the narcotic pain reliever fentanyl, rose 45 percent. Such deaths have increased tenfold in the past five years.

More:Alcohol is killing more people, and younger. The biggest increases are among women

More:Suicide rate up 33% in less than 20 years, yet funding lags behind other top killers

More:Suicide prevention experts: What you say (and don't say) could save a person's life

Loribeth Bowman Stein says the lack of social connection fuels hopelessness: "We don’t really see each other anymore."

"We don’t share our hopes and joys in the same way, and we aren’t as available to one another, physically and emotionally, as we need to be," says Stein, of Milford, Connecticut. "The world got smaller, but lonelier."

Miller agrees. When people feel a "lack of belonging," he says, "they seek meaning in other places."

That can lead them to withdraw into addiction. The new report emphasizes what should be done differently.

Kimberly McDonald is a licensed clinical social worker who has worked in a hospital, for county government and in private practice. She lost her father to suicide in 2010.

"We are a society that criticizes and lacks compassion, integrity, and empathy," the Richmond, Wisconsin, woman says. "I work daily with individuals who each have their own demons."

McDonald's father took his own life after diagnoses of Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease.

"He knew the trajectory of where the disease would take him," she says.

John Auerbach, the former Massachusetts state health secretary who heads Trust for America's Health, says the country needs to better understand and address what drives "these devastating deaths of despair.”

If you are interested in connecting with people online who have overcome or are struggling with issues mentioned in this story, join USA TODAY’s "I Survived It" Facebook support group.