“If Michelle Obama had had natural hair, Barack would not have won.”

This is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie speaking, a Nigerian author best known for her book (and subsequent movie) One Half Of A Yellow Sun and, of course, the excerpt from her TED talk on feminism which features on Beyoncé’s 2014 track ***Flawless. Ngozi Adichie isn’t the first person to have strong opinions relating to black women’s hair, but this one did stand out - and the more I thought about it, the more I agreed with her sentiment.

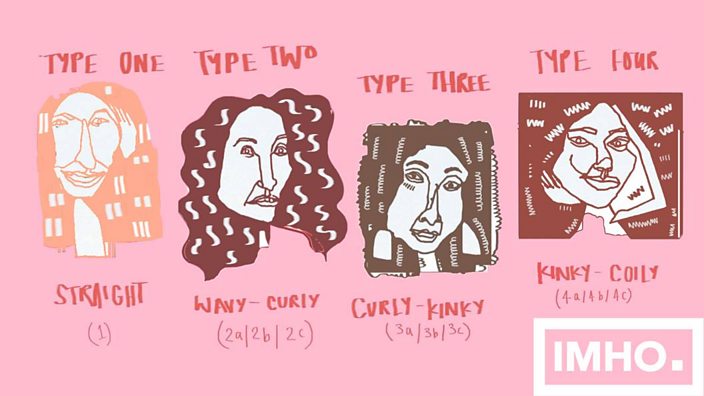

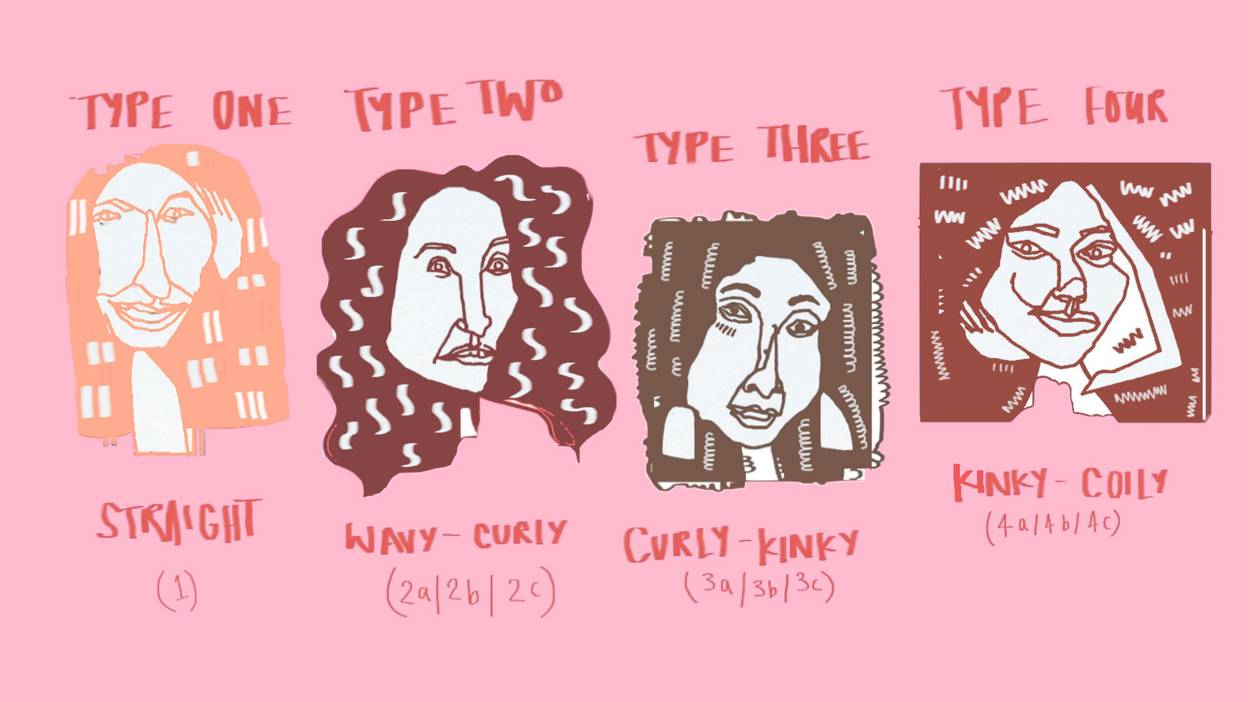

Behind pretty much every black woman’s coiffure is a story of trauma. In particular, those of us with ‘4C hair’ - the tightest type of curl - don’t have the luxury of not caring about it. If it’s not combed, it becomes a tangled mess, with naturally forming dreadlocks having to be actually cut out of it. If it’s not oiled and moisturised, it can break off in chunks. Braiding takes hours, and can be painful if the hairdresser is inexperienced (or mean).

When I was eight years old, my mum gave me an ultimatum. Either, she said, you shave your hair off like mine, or, I’ll put your hair into dreadlocks. My brown afro, not at all resembling archetypal mixed-race hair, was thick, tightly coiled, and - as both me and my mother knew after hours of screaming, tugging and arguments - painful to have combed and braided. I chose the second option - dreadlocks, and have never laid eyes on my afro since.

I’m not alone in this experience. Most black women in the UK do not wear their hair completely naturally all of the time, and there’s a whole other language to learn surrounding the practices we use to manipulate it. We plait our hair into 'box braids' with synthetic skeins of shiny plastic, or sew other women’s hair onto our heads in 'weaves'. We 'relax' our hair - burn it straight with creamy chemical straighteners - or 'texlax' it into slick curls.

Leyla Reynolds

Leyla Reynolds

Ngozi Adichie’s comments, alongside the internet trolls who recently descended to criticise American Olympic gymnast Gabby Douglas’s hair for being frizzy while performing, reminded me that our hair is still open to scrutiny in the Western world; as if our appearance must be validated before we are as people. This comes from both the white and the black community – but, as with so much of our past, its history is connected to colonialism, slavery, and our attempts to make blackness 'acceptable' in the post-emancipation era.

There hasn’t been a huge amount of history or research looking into black hair practices, but in Ayana Byrd and Lori Tharps’s book Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America, it’s explained that one of the reasons we have been manipulating our hair for so long is that, “slaves living in plantations soon realised that lighter-skinned blacks with straighter hair worked inside the plantation houses performing less backbreaking labour.” After slavery was abolished, straight hair became a way of us conforming to white standards of beauty. The conk, a burning mixture of potato, egg and lye (a chemical still used in modern-day hair straighteners), was invented - giving us the glossy locks we desired - alongside the 'hot comb', old-fashioned hair straighteners.

Leyla Reynolds

Leyla Reynolds

It’s clear that the pressure for black people to manipulate their hair out of its natural state is still strong. This is evidenced by stories such as that of Bournemouth University graduate Lara Odoffin, who had her job offer revoked owing to her braided hairstyle; or that of Disney star Zendaya, whose wearing of faux dreadlocks on the red carpet led one commentator to suggest she might smell like weed. Often traditional hairstyles and afros are deemed unprofessional or 'radical', and in 2014, cornrows, braids, twists and dreadlocks were even briefly banned by the US army. This is why, as Ngozi Adichie says, Obama may have struggled to win the election with a wife who wore her hair naturally. Despite the fact it grows out of our heads, it is viewed as an anomaly - below the standard of mainstream regard.

But things are changing. Market research firm Mintel has estimated that the black hair business, which is worth roughly £596 million, is going to see relaxer sales decrease by 45 percent before 2019. While in the past, black people in the UK like myself have struggled to get hold of natural hair products, there’s recently been a huge surge in goods available, even in the more mainstream outlets.

Oyin Akiniyi, the founder of The Good Hair Club, says that for many black women, hair care has become more than just functional - it is a celebration of who we are on our own terms: “As a consumer group black women are often ignored or underrepresented in mainstream beauty experiences and, at the same time, the retail landscape for black hair is dominated by individuals who neither understand black hair women or care to offer experiences that reflect who she is,” she says. “The need for a public celebration of diverse beauty has never been stronger; we want to begin positive dialogue about black beauty experience that is authentic and represents the black British female experience."

The natural hair movement, which officially became mainstream when Beyoncé sang about liking her daughter Blue Ivy’s “baby hair and afro” on Lemonade's Formation, has taken over and changed the way many black women like Oyin (who shaved off her relaxed hair a few years ago) think about their afros. Instead of being a burden, they have become a project, a labour of love. Bloggers and vloggers are cited as being inspiration for many women to start wearing their hair naturally.

Leyla Reynolds

Leyla Reynolds

Although, of course, not all women feel pressured into straightening their hair, or wearing weaves (like myself, they might do it for ease), there is no separating our current hair-care regimes from their colonial past. It can only be positive that black women are becoming more comfortable with their afros, and learning how to take care of them effectively after so many years of racist dialogue suggesting that they were a negative thing.

And while at present I’m still relaxing my hair, I’ve made a promise to myself. By the time I’m 30 I want to see my afro again.