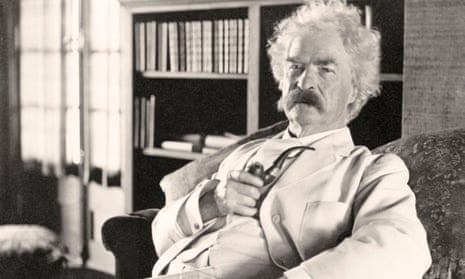

What if you could make a list of everything Mark Twain ever read and of every book he ever owned? Dr Alan Gribben, cofounder of the Mark Twain Circle of America, has spent the last 45 years doing just that. But why? For more recent authors such as Philip Roth or John Updike, the idea of chronicling their reading isn’t unusual: Roth willed his book collection to Newark Public Library in New Jersey; Updike’s went to Harvard University’s Houghton Library. But Roth and Updike were both a different sort of writer. They lived in our era, and on land. As a steamboat captain, Twain – real name Samuel Langhorne Clemens – lived on the river, his life and work in constant motion as he authored travelogues, time-travel novels and adventure stories about runaway slaves. Would he have wanted a list out there, nailing down the precise location of every book he had owned?

Whether he would or not, literary scholars do. In the New Historicism school of literary thought, writing is examined in its authorial context. Heaven forbid someone read Twain’s story The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County and think it’s just a funny tale. To understand it, New Historicists must know everything frog-related that could have been in Twain’s mind while writing. What was the sociopolitical perception of frogs in 1865? Did Twain keep a pet amphibian as a child? What books did he read about frogs?

Answering the last of these questions has been difficult. In addition to riverboating, Twain held other jobs that required travel: prospector, reporter, lecturer. Logistically, he couldn’t keep many books and those he did carry were often lost. A trunk’s worth disappeared on one transatlantic voyage, and he once recalled leaving a copy of Robinson Crusoe on a train. Twain’s daughter, Susy, once described him as “the loveliest man I ever saw, or ever hope to see, and oh, so absent-minded!”

In Twain’s defence, many other famous writers made work hard for scholars by misplacing their books. F Scott Fitzgerald lost his between moves, and Ernest Hemingway left an untold number in Cuba. As a result, between the 1940s and 60s, explains Gribben, “meticulous studies [were] initiated to identify the contents of ... major American authors’ libraries”, cataloging what Ralph Waldo Emerson, Herman Melville, Emily Dickinson and others had read. Yet somehow Twain got left out and, as Gribben notes, those studying him “had to check dozens of disparate sources that revealed bits of his literary knowledge”.

Well, not anymore. In Mark Twain’s Literary Resources, a three-volume work of literary criticism to be published in May, Gribben outlines the reading that influenced Twain, from Shakespeare to Poe. While scholars will certainly benefit, the book itself is more than academic. It’s a labour of love, with Gribben describing how he uncovered Twain’s tomes in basement boxes, even finding some in sacks by the side of a road. He also had to navigate fakes, books with counterfeit autographs and annotations made by the notorious forger and murderer Mark Hofmann.

During his life, Twain could be evasive about his reading, claiming in 1886 that he couldn’t name 100 authors. Other times, he willingly shared his habits with the press, telling New York World Sunday Magazine precisely how many hours he read each day, at what time, and where.

“Perhaps it is some type of karma that this well-travelled writer should have his family’s library collection spread out across the land,” says Gribben, noting the Twain family owned more than 3,000 books, and the humourist is known to have read nearly 5,000 literary works.

This, Gribben states, may make doubting critics see Twain as a great author, not merely a funny man from Missouri. History may not have preserved writers’ libraries as we now do, but there is one thing about literaria that hasn’t changed – the false notion that great words only come from those in the right places.

“Twain was, from the beginning, dismissed by many elite critics,” Gribben says. “Even today, there are those who look down their noses at Twain as an unrefined upstart, a lucky opportunist who gained fame merely on the basis of his outrageous humour.” By proving Twain read the greats, Gribben shows the world he was one.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion