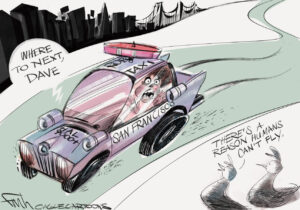

All Hail the Ride-Share Strike

Company executives make huge profits at the expense of drivers and customers. Now unions are striking on the eve of Uber's IPO. Shutterstock

Shutterstock

The ride-hailing company Uber is making its initial public offering (IPO) on Friday. Executives are hoping for a whopping $91 billion valuation, which The New York Times said would be one of the largest in tech industry history. Uber says it has set aside about 3% of its shares for its drivers and will also be handing out “driver appreciation awards,” an obvious ploy to whitewash the poor conditions and wages under which drivers say they are forced to work.

Uber and Lyft drivers have been agitating for years to be recognized as direct employees rather than independent contractors. Los Angeles drivers have organized a 25-hour strike for May 25 to protest the 25% pay cut Uber recently announced. Workers in such cities as Los Angeles, New York, Chicago and San Francisco are building on that action with a one-day strike on Wednesday, timed within days of Uber’s IPO.

James Hicks, a driver and organizer with Rideshare Drivers United-Los Angeles, told me in an interview that “we’re striking again because our demands were not met by Uber or Lyft, and so we’re going to put more and more pressure on them.”

The idea behind a strike—whether it is done by union or nonunion employees—is that workers use the greatest leverage they have to make their demands, which is the withholding of their labor. The point is inconvenience and a loss of profits for the employer. Hicks said that on March 25, there were longer wait times for rides because fewer drivers were on the roads.

Drivers are angry and eager to organize. In late March, Rideshare Drivers United had about 2,800 members. Today, according to Hicks, the L.A. group’s ranks have swelled to about 4,500. The drivers have joined forces over a set of demands they call the Drivers’ Bill of Rights. Their first demand is for fair pay. They want the standards that New York City drivers recently won: a base salary of $27.86 an hour, which works out to about $17 an hour after deducting expenses. Not only do drivers want to be paid for the time it takes them to reach riders, they want a 10% cap on the commission their employers take.

One could reasonably argue that for the service of connecting drivers and riders through an easy-to-use app, a 10% commission cap is eminently fair. As it stands now, according to Hicks, the companies are “stealing upwards of 40% to 60%” of fares. Rideshare Drivers United encourages drivers to post screen grabs of their receipts online to showcase the egregious Uber and Lyft commissions. One example showed a customer paying $41.18 for a ride for which the driver got only $3.52 after Uber’s cut. That’s more than a 90% commission rate. As Hicks concisely put it, “That’s price-gouging on the consumer side, but that’s also wage theft on the employee side.” Meanwhile, Uber’s top five executives made $143 million in salary and stock options last year alone.

The stock options for drivers Uber has been advertising ahead of its IPO are “just PR,” Hicks said. “The drivers being disgruntled is a huge problem for Lyft and Uber. They’re trying to give us 3% only as a means to shut us up, when what we really want is a living wage.”

Ride-hailing drivers are part of the so-called gig-economy that corporate America has sold as a better version of the American Dream. The idea that workers can be their own boss because they set their own hours was sold as a modern idea whose time had come. But the uncertainty of the work and low wages have turned gig-economy jobs into a nightmare. Added to the poor pay is job insecurity, because drivers can be dropped or “deactivated” without due process if a rider makes a complaint. Hicks told me about a rider who complained that Hicks had been smoking marijuana while driving when he had done no such thing; Hicks had picked up an earlier rider who had smoked pot, bringing the distinctive smell into the car and leading the next passenger to assume that Hicks had been the one smoking. When Hicks was locked out of the app with no explanation, he had to beg to be reactivated.

Drivers are also demanding that Uber and Lyft enable them to see the potential fare and percentage of take-home pay from a ride before accepting it. And they want riders to be able to see the fare breakdown, so that the corporate commission is clearly visible to consumers. Both of these demands protect the dignity of drivers and riders.

Ultimately, drivers have a long-term goal in mind through their one-day strikes: to unionize. “We admire unions,” Hicks said. “Unions protect workers from greedy bosses; they protect us when we are injured or are terminated without cause.” He added, “Unions are very important to the foundation of the working class in America, and it’s time for us to have our own voice.”

In California, ride-hailing corporations are already operating in a legal grey zone by refusing to treat their workers as employees. California’s Supreme Court issued a ruling last year in the case of the courier company Dynamex, saying that companies have to treat their workers as employees rather than independent contractors.

That law applies to ride-hailing companies, too, Hicks believes. “They are both breaking the law,” he said of Uber and Lyft. “I know that’s strong language, but it’s true.” By insisting on counting drivers as independent contractors, the companies save money on mandatory benefits such as disability insurance. While the state is moving to embed the Dynamex court ruling into law, Uber and Lyft have rushed to sell stocks in their corporations, hoping to outrun labor laws.

The tide is turning, however. As ride-hailing becomes more ubiquitous around the country, the ranks of disgruntled drivers are growing and gaining the sympathy of consumers and politicians. California Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, for example, who has authored the bill encompassing the Dynamex decision, said Uber and Lyft are unlikely to be exempted from its requirements. Gonzalez, who has shown her support for ride-hailing drivers, says she’s not worried about the corporations’ bottom lines. “Am I concerned about the stock price of Uber and Lyft? No. It doesn’t keep me up at night,” she said. Perhaps it is the executives of the ride-hailing companies who are suffering from sleepless nights as drivers plan even more strikes until their demands are met.

Watch Sonali Kolhatkar’s interview with James Hicks about the ride-share strike (via “Rising Up With Sonali”):

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.